RIVER

GODDESSES

Water is considered sacred throughout human history and in most cultures. As flowing water, rivers are commonly associated with nurturing the living and carrying the departed.

In South Asia, there is a strong and ancient belief in the sacrality of the river, especially her ability to cleanse sin and help the deceased to attain liberation (moksha in Sanskrit). This belief is vividly articulated in the popularity of river goddesses, like Ganga and Yamuna. In the early nineteenth century painting from Jaipur, the goddess Ganga holds a water pot like the women fetching water. While the Jaipuri painting shows Ganga frontally as if revealed inside a shrine with a rolled- up screen, in M. F. Husain’s Mahabharata series, Ganga and Yamuna are youthful damsels facing each other in opposite directions. Yamuna’s gaping mouth and the silent scream of Satyavati swimming in the Yamuna seem to anticipate the river’s extreme pollution that urged contemporary artists like Atul Bhalla ( see his work in the exhibition) and Ravi Agarwal ( i.e. Yamuna Manifesto, 2013) to engage with ecological issues around the Yamuna river. [JK]

Artist once known in Jaipur, India

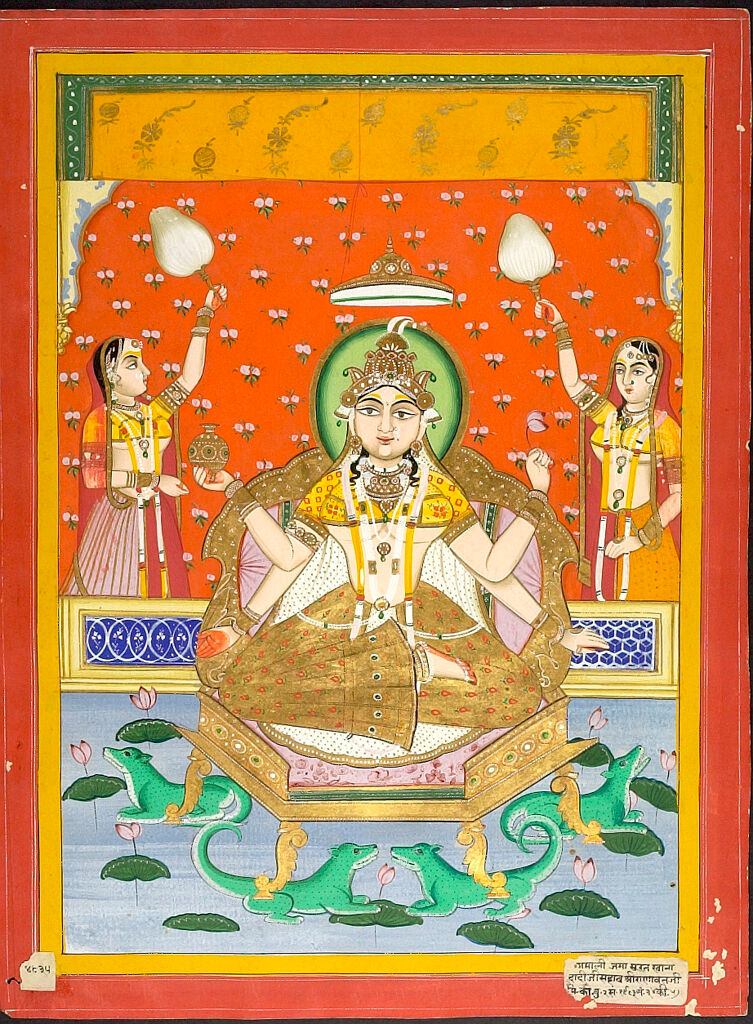

Hindu Goddess Ganga with Two Female Attendants Carrying Fly-Whisks

Artist once known in Jaipur, India

1826

15 ¾ x 11 13⁄16 inches

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of James E. Robinson III in honor of Stuart Cary Welch and Alve John Erickson, 1997.236

In this early nineteenth century painting from Jaipur, India, the river goddess Ganga sits frontally on a golden throne floating in a lotus pond. The identity of the four-armed goddess as Ganga is conveyed through a water pot that she holds in her raised right hand along with her trusted vehicle, makara, a mythical aquatic creature, here multiplied in four as if supporting four legs of her seat and represented in brilliant green using a newly introduced synthetic pigment. Ganga is bedecked in jewelry, including multiple strands of pearls that are voluminously painted as raised white dots and emerald and pearl studded golden ornaments. Two maidens, also dressed in finery, wave fly-whisks on either side of her behind a banister. Historically, Ganga was most often depicted as standing in tribhanga (i.e. contrapposto) on makara holding a water pot as if alluding to the myth of the celestial river’s descent.

A seated, frontal image of the goddess and flat picture plane may make the painting appear static at first glance, but the artist ingeniously portrays a delicate movement and passage of time: asymmetrical position of the fly whisks held by the attendants signals their waving while the three-quarter profile view of the lady standing to the left of Ganga ( right side of the painting) breaks the symmetry common in paired attendant figures to a frontally facing image of a deity. Even the makara under Ganga’s lower left hand bellows out a cry stirring the quietude. Above the goddess, the rolled up yellow screen tied with red cord suggests that this vision of the goddess may be viewable only temporarily. All the golden ornaments both on the goddess and the attendants are rendered in actual gold and the goddess’ skirt and the throne are painted in gold that shimmers under raking light—this is best observed from below when viewing the painting on the gallery wall. The sheer red sari of the attendants and the style of the jewelry are similar to those seen in early photographs of Jaipur royal women taken by the Jaipur’s Rajput king, Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II in the 1870s. The extensive use of gold and Indian yellow, the brilliant yellow pigment made of cattle urine along with newly available synthetic artificial pigments like Emerald Green and Prussian Blue most likely imported from Europe suggest that the painting served an affluent devotee. [JK]

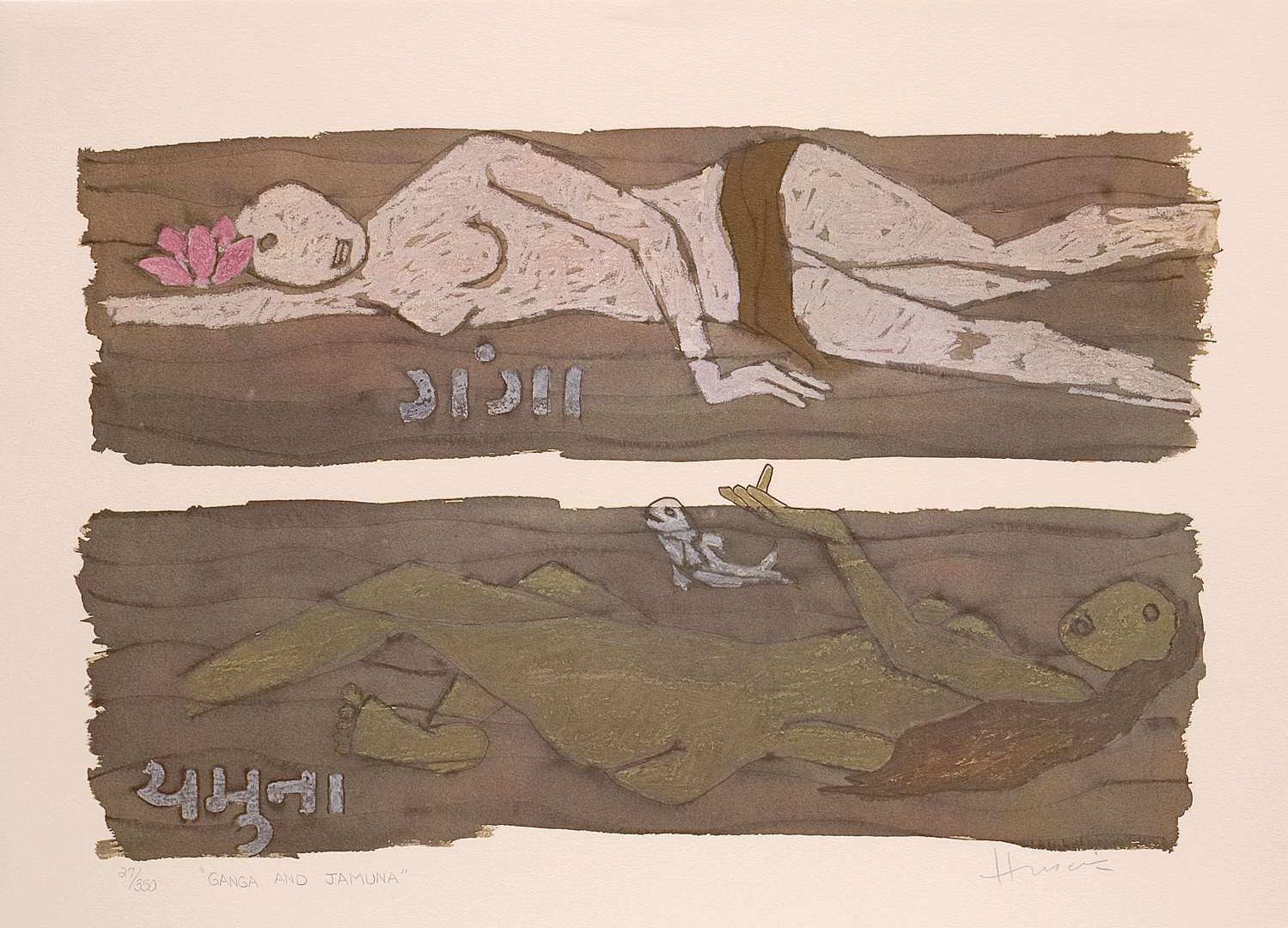

Maqbool Fida Husain

Ganga and Jamuna, Mahabharata series

Maqbool Fida Husain (Indian, 1915-2011)

after 1983

sheet: 17 ½ x 24 inches

Serigraph, ink on paper

Peabody Essex Museum, Gift of the Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, 1995 E300019.12

Lifelines of several civilizations and timeless inspirations of piety and transcendence, Ganga and Yamuna are the two Himalayan rivers that make fertile the plains of north India and drain into the Bay of Bengal. Their divine waters wash away sins and offer release from the cyclical sufferings of existence. Often depicted as youthful damsels, these river goddesses appear in several Indic mythologies and the artistic traditions derived from them. Hussain paints the two rivers as young maidens facing each other and floating in opposite directions in the undulating swells of their waters. Ganga is fair with a lotus near her head, symbolic of spiritual transcendence, and Yamuna is dusky with hair let loose and a fish frolicking out of its waters.

In the Indian epic Mahabharata, both Ganga and Yamuna play significant roles in building the Kuru lineage. King Shantanu first marries Ganga and then Satyavati who was born of a fish caught in the waters of Yamuna. Ganga’s son, Bhishma, vows celibacy and abdicates the throne in favor of Satyavati’s sons, and is often obliged throughout the epic to act as the Kuru clan’s guardian. In moments of moral dilemma, Ganga’s son sets the standards for the descendants (via Satyavati) of Yamuna. Hussain’s composition is an ode to this relationship between the two rivers. While Yamuna’s flow is synonymous with Satyavati’s long lineage in the epic, Ganga’s flow in the opposite direction evokes Bhishma’s celibacy and his unwavering efforts at reversing the vagaries of the former’s descendants. This is further exemplified by Yamuna’s raised left hand seemingly in the shape of a lamp, symbolic of her progeny, which is kept un-doused by the cupped hand of Ganga. Together the two rivers stand at the origins of the epic war of the Mahabharata, fought for the Kuru kingdom that spanned the land between the two rivers. [RA]

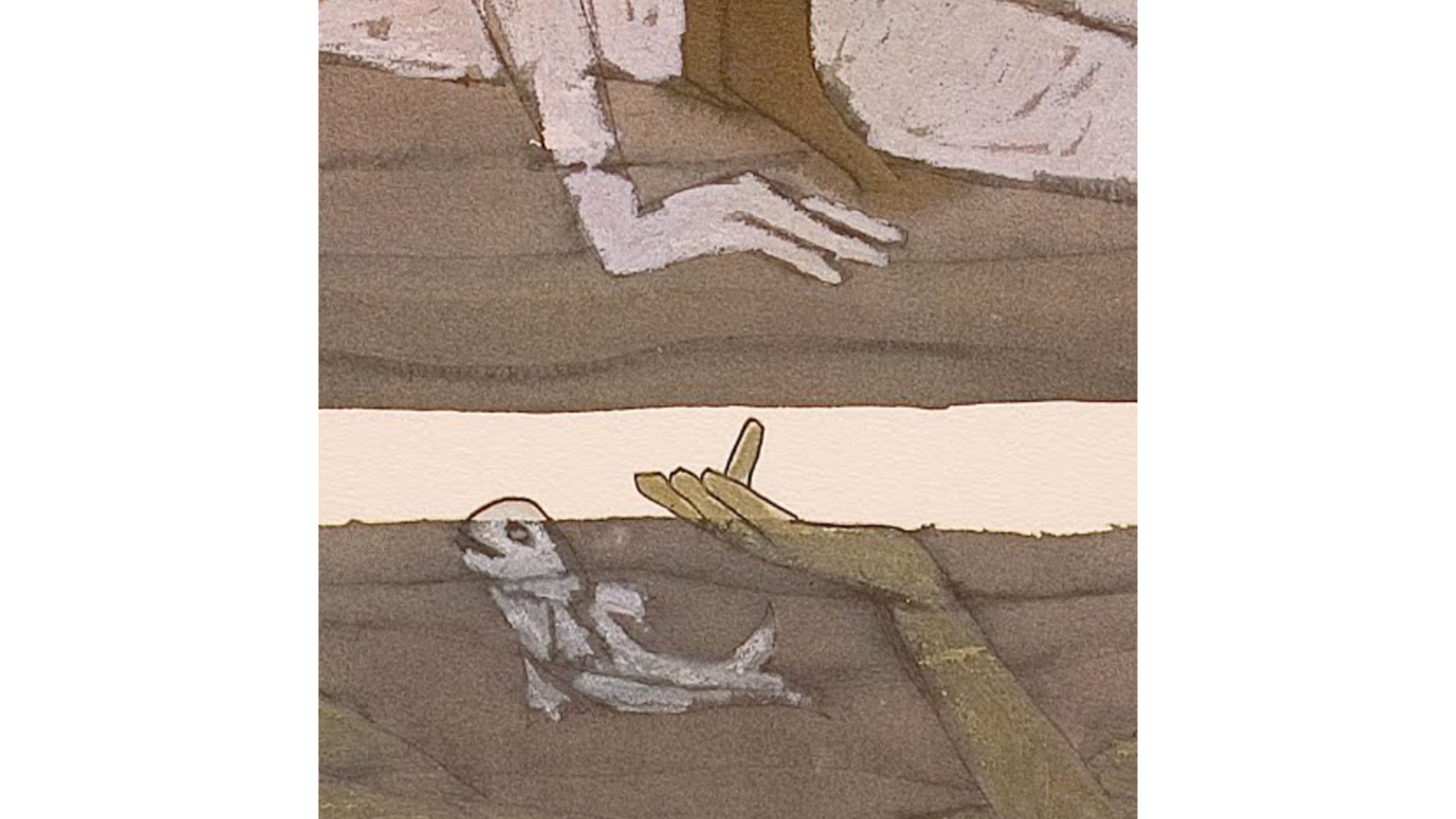

detail

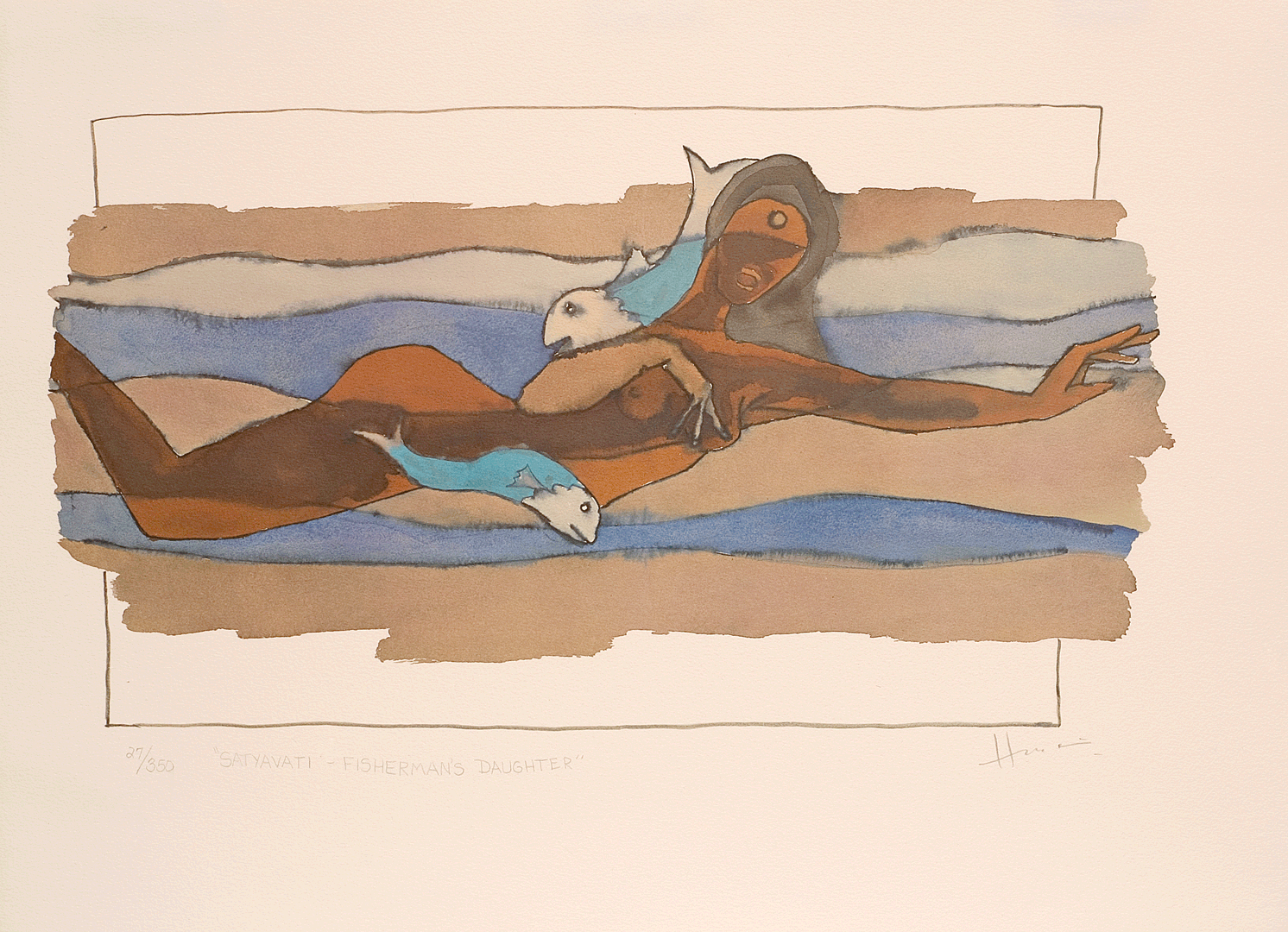

Satyavati-Fisherman’s daughter, Mahabharata series

Maqbool Fida Husain (Indian, 1915-2011)

after 1983

sheet: 17 ½ x 24 inches

Serigraph, ink on paper

Peabody Essex Museum, Gift of the Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, 1995 E300019.3

Satyavati, who would go on to marry King Shantanu of Hastinapur and become the queen of the Kuru kingdom, was the daughter of a humble fisherman and lived by ferrying travelers across the banks of the river Yamuna. Legend has it that she was born of a celestial nymph who had been cursed to live like a fish in the Yamuna. When caught by the fisherman, the fish was cut open to reveal Satyavati and her twin brother. As a daughter of the nymph Satyavati attained unparalleled beauty, and just like the river, she was dark-skinned and called Kali. Born of a fish, however, she was to forever carry its stench and hence called Matsyagandha, “she who smelled of fish”.

Husain depicts Satyavati as a young damsel swimming in the waters of Yamuna. Two fish frolic off her sensuous body and evoke her scent. We catch her in the act of swimming, her lips gape open and arms stroke forward, and her body glides through the undulating swells of the river. Such was her beauty that she was desired twice for a companion in the epic Mahabharata. Once by sage Parashara, who magically rid Satyavati of her stench and blessed her with everlasting sweet fragrance, and for the second time by king Shantanu who made her his queen. To the sage, she bore Vyasa, the author of the Mahabharata, and to the king, two sons Chitrangada and Vichitravirya. In Vichitravirya’s lineage are born the hundred-and-one Kauravas and the five Pandavas, whose feud for the kingdom causes the great war of Mahabharata. [RA]

detail

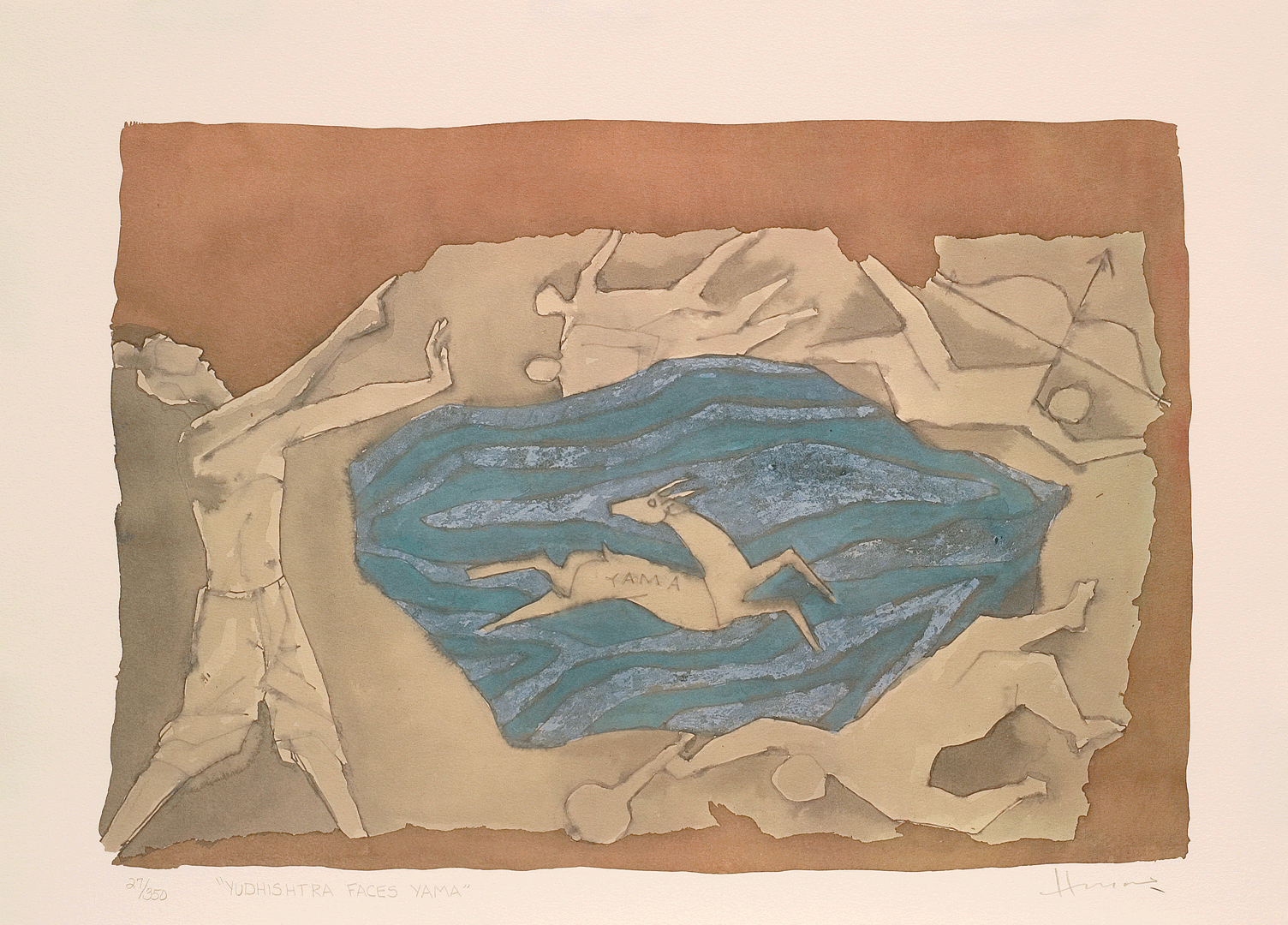

Yudhishtra faces Yama, Mahabharata series

Maqbool Fida Husain (Indian, 1915-2011)

after 1983

sheet: 17 ½ x 24 inches

Serigraph, ink on paper

Peabody Essex Museum, Gift of the Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, 1995 E300019.5

Upon losing their kingdom in a game of dice, the Pandava brothers along with their common wife, Drauapadi, lived in exile in dense forests for 12 years. Once while residing in the Dvaita forest, they were requested by a hermit to chase after a deer that had stolen his fire-kindling wood. The five brothers were led into deep interiors of the forest before they finally lost track of the deer. Exhausted, the eldest of them, Yudhishthira, asked Nakula to go in search of water. When Nakula didn’t return in time, Yudhishthira sent their youngest brother Sahadeva to look for him. When he, too, didn’t return, Arjuna and later Bhima were sent in search of water and their missing brothers. Worried by the delay in return of all his brothers, Yudhishthira himself set out to look for them, only to find them dead before a crystal-like lake. A voice of a Yaksha, a semi-divine being, in possession of the pond, tells Yudhishthira that none of his brothers had paid heed to the Yaksha’s questions and drank from the pond without his approval. Yudhishthira agrees to answer the Yaksha’s questions and eventually wins back the lives of his brothers.

Inspired by this tale from the Aranya Parva (Book of the forest) of the Sanskrit epic, Mahabharata, Husain depicts the moment when Yudhishthira arrives at the pond and laments at the sight of his heroic brothers lying motionless. Dressed as an ascetic with his matted locks tied in a bun, Yudhishthira is seen pointing to the sky from where the voice of the Yaksha is heard. Husain paints the sky in a wash of dull ochre that surrounds the composition, and from where we get a bird’s-eye view of the four brothers laid in death. Hussain’s genius in this composition lies in inverting the gaze from the earth to the sky, in that, each of the dead brother is made to resemble a constellation that complements their personalities – the twins Nakula and Sahadeva as Gemini, the great archer Arjuna as Orion and the mighty Bhima with a club as Hercules. At the center of this painting is the deer that started this episode, still running away and looking back at Yudhisthira in the swirling blue water of the lake. Impressed by Yudhishthira’s answers, the Yaksha revives the four brothers and reveals that it was he who had taken the form of the deer in the first place.

An inscription on the deer and below, however, identifies the Yaksha as Yama, the god of death. By identifying the Yaksha-deer as Yama, Husain creatively recalls another episode towards the end of the Mahabharata in which Yama tests Yudhisthira by following him in the form of a dog for whom Yudhisthira declines the opportunity to ascend to heaven. More than thirty years since the initial creation of Husain’s Mahabharata series, which started in 1971 as oil on canvas painting, the god of death appearing as deer in the middle of a lake surrounded by slain heroes of the epic under the brown sky bears an uncanny resonance to the climate disasters we face today. [RA]