FLOWING

STORIES

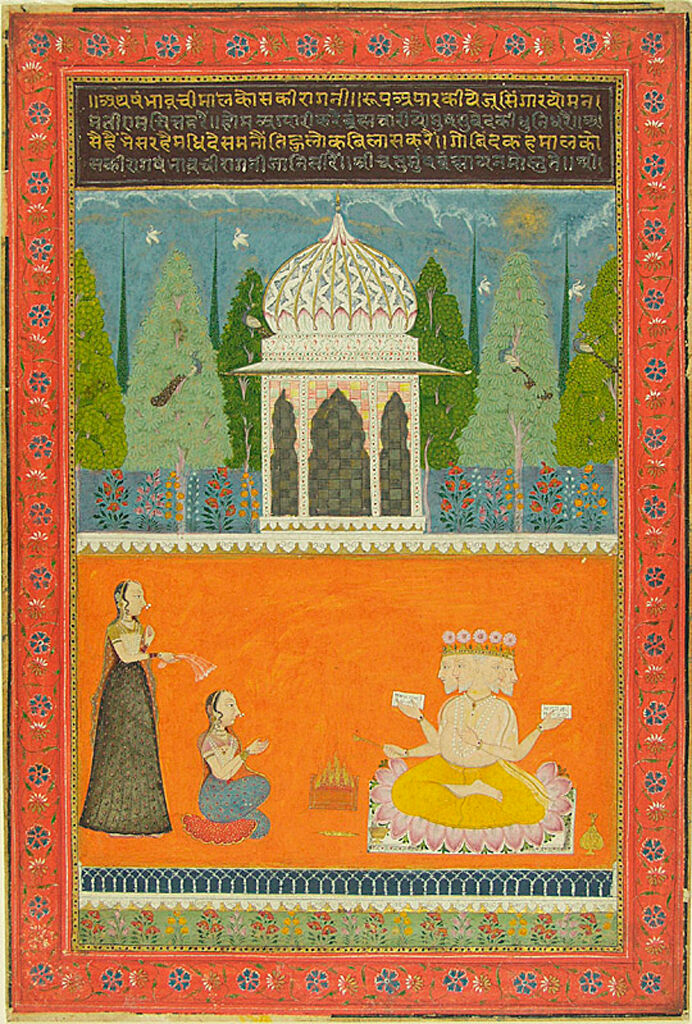

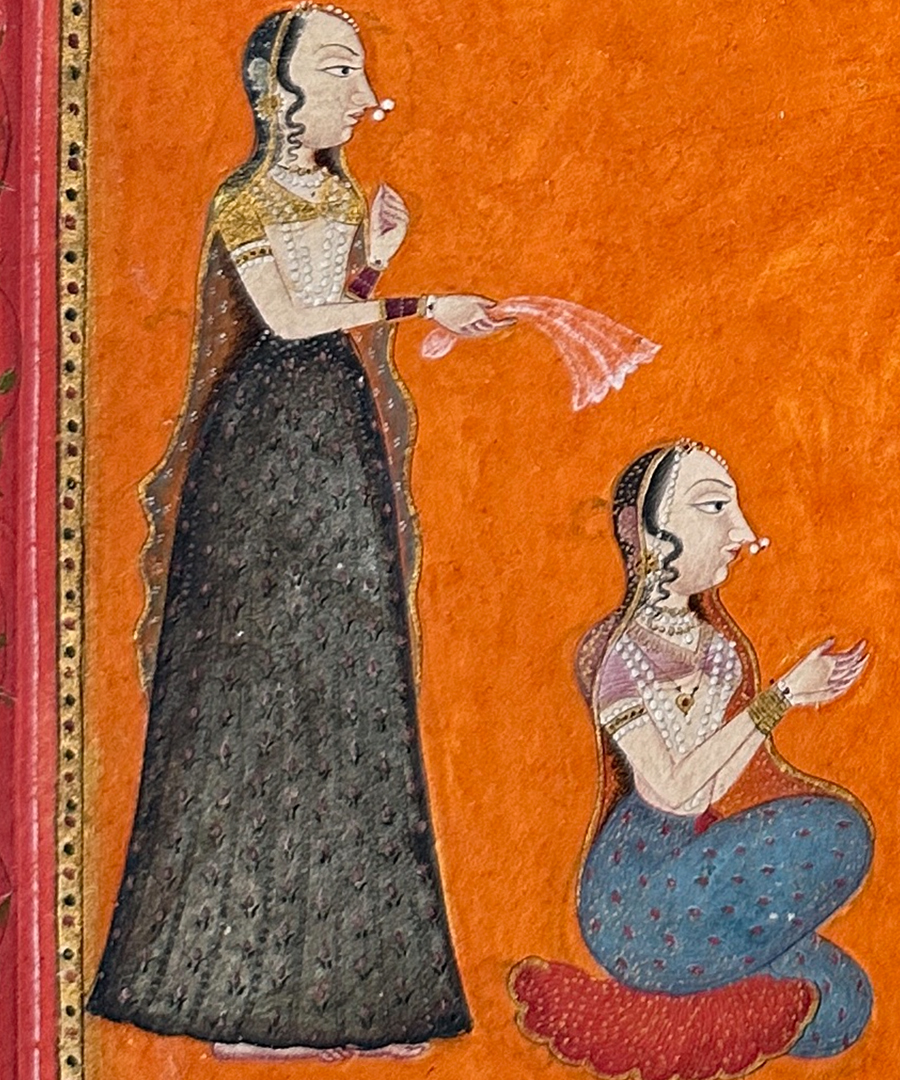

The set of three paintings from India belongs to a “picture book” of the Ragamala, Garland of Musical Modes (rāga means musical mode or melody). A picture book (literally citrapustaka according to the colophon on the back of the Asavari Ragini folio) of the Ragamala is a compilation of paintings that portray musical modes through figurative means. Pictorialization of each musical melody or raga allowed aesthetic appreciation and sharing of the transient experience beyond temporal and spatial limits. The Ragamala paintings began to appear in the dominant cultural practices of Northern India during the sixteenth century, quickly becoming popular in various regional courts. The artist, Jaikishan pays homage to the first musical mode, the Bhairava Raga through the origin story of the Ganga River: the celestial river descended on earth through Shiva mitigating her fall, here uniquely represented through the dancing body of half-Shiva, half-Parvati against a luscious green backdrop. The book ends with the Asavari Ragini controlling snakes through music, evoking nagas (serpentine beings) that control the water. While the Ragamala is not necessarily about water, such musical performances were often held by a body of water, as seen in a painting of a courtly lady performing music by a lake, now on view at the Harvard Art Museums (until October 2023).

The vibrant colors of Jaikisan’s paintings find resonance in exquisite color-pencil drawings by the contemporary artist Evelyn Rydz whose multidisciplinary practice centers around water. Her painstaking rendering of disintegrating marine ropes subverts rapid cycles of capitalist consumerism polluting our waters while the paper sculpture from her Open Oceans series creates a new body of connected waters, generating new stories of im/migration and climate change. Various waters and the debris collected along the shores are transformed into an intricate drawing in her “Unfolded Waters” series that also speaks of connectivity and human impact on water. Although Evelyn Rydz and Jaikisan are nearly three hundred years apart and more than seven thousand miles away on the opposite side of the globe, their shared artistic ethos, such as meticulous approach to rendering small details and creative use of brilliant colors, making us see the shape and the color of waters and hear the stories that they each tell through their art. [JK]

Jai Kisan of Malpura

Ardhanareshvara (Half-Shiva, Half-Parvati form of Shiva dancing with Ganga flowing from the top knot),

from a Ragamala (Garland of Melodies) Series

Jai Kisan of Malpura

c. 1756

12 1⁄16 x 8 1⁄16 inches

Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and beetle shell on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Eric Schroeder, 1969.174

Can you hear the gushing water streaming from the top knot of the conjoined body of Shiva and Parvati? As the foremost and first raga in a series of ragas, Bhairava Raga is traditionally the first raga a student of classical Hindustani music learns. The music is described as solemn and peaceful, and it is to be performed at the daybreak. Bhairava is a wrathful form of the Hindu God Shiva. Most known Bhairava Raga paintings of the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries depict Bhairava as Shiva seated with his wife, Goddess Parvati, inside a palatial setting. Here, the Malpura artist Jaikisan ( written as “Jaikisna'' in the colophon) took a unique approach to representing this foremost raga, representing Shiva and Parvati in one body in the form known as Ardhanareshvara (literally, the lord who is half-woman), that too, dancing, indicated by the bent knees and raised arms.

DETAIL ONE

DETAIL TWO

At first glance, one only sees blue Shiva whose head is in profile but soon it becomes clear that the left side of the figure is of the Goddess Parvati. Subtle blending of two bodies of male and female is remarkable: Shiva’s orange dhoti ( a man’s lower garment) and Parvati’s red skirt painted in vermilion are seamlessly conjoined. On the upper body, a deer skin garment across the chest and a snake that envelopes around Pavati’s torso are all Shiva’s iconographic attributes, so are the handheld drum in his right hand and the trident in her left hand. The artist rendered their hair colors differently: Parvati’s long and curly black hair cascades down behind her back while Shiva’s light hair blends into his skull necklace. As if to signal the beginning of all ragas, the story of the descent of Ganga is evoked through a stream of water spouting from a conjoined, non-dual form of Shiva who also carries a distinct mark of crescent moon on his forehead. In response to the prayers of a sage Bhagirath who sought salvation of his deceased ancestors with Ganga water, Shiva agrees to intervene to break Ganga’s fall from the sky that would otherwise have caused a deluge on earth. The water gushes out of the top knot of Shiva’s hair, which is distinctly marked in green using a piece of beetle wing fragment. Along with the sound of the water that’s dwarfing the valleys and hills that the river flows through, we can almost hear the roar of the tiger, the goddess Parvati’s vehicle, and the rhythmic tapping of Shiva’s bull whose right leg is bent and raised. The celebratory mood is further enhanced by the two peacocks on either side of the background landscape: they seem to call on the impending monsoon rain ( peacock’s calls are traditionally associated with the arrival of monsoon rains). The accompanying text on top offers a hymn and a salutation to lord Shiva whose form is described. [JK]

Khambhavati Ragini, from a Ragamala (Garland of Melodies) Series

Jai Kisan of Malpura

c. 1756

12 ½ x 8 ½ inches

Ink, opaque watercolor, gold on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Eric Schroeder, 1960.681

Khambhavati Ragini (a female counterpart of a male raga, in this case named Malkosh, belonging to the classical Hindustani music’s classification system) is often pictorialized as a beautiful maiden paying homage to the Hindu god Brahma who’s officiating a homa (vedic fire ritual). This raga is performed in autumn, post-monsoon in early evenings. The setting is on a terrace with a pavilion overlooking a garden, most likely with water nearby since most early Khambhavati Ragini paintings depict the scene by a body of water with a plentiful of fish, as if indicating the boon of fecundity granted by Brahma, depicted here as a four-headed, four-armed white bearded male figure seated on a lotus holding two books. Upon close inspection, it is clear that the artist tried to differentiate the area between the tree canopies and the railing from the sky by adding subtle striations in darker red hue.

DETAIL ONE

DETAIL TWO

The painting showcases Jaikisan’s artistic bravado, especially his fine hand in handling minute details, including subtle shading of physiognomy, raised pearls, jewelry, different types of flora and trees. The delightful patterns on the pavilion are exquisitely painted using precious materials - the shaded archways are painted in silver with alternating gold and black ink striations, while the zigzagging blue patterns around golden ribs are painted most likely in smalt (a cobalt-based glassy blue pigment) that looks glistening under lighted magnification. The smiling sun’s ray shines through clearing clouds as if celebrating the arrival of autumn. In fact, the sky under the cloud shimmers thanks to the subtle wash of shell gold pigment over the blue sky. The standing female companion’s blouse is painted in shell gold as well, and her sari and skirt that appears dark gray is in fact painted in silver which has since tarnished. Every jewelry and trims of garments on all figures are painted in shell gold. The entire inner border is a thin strip of gold, and even some petals of frolicking flowers set against a red border painted in vermillion are done in shell gold. Such generous use of precious materials like gold and silver and diverse range of pigments, including three different red pigments ( vermilion, red lead, and organic red) speaks to the sumptuous courtly context of mid-eighteenth century Rajasthan in which this extraordinary picture book of the Ragamala was prepared and enjoyed. [JK]

Asavari Ragini (painting, recto; text, verso), from a Ragamala (Garland of Melodies) Series

Jai Kisan of Malpura

c. 1756

12 7⁄16 x 8 7⁄16 inches

Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of Eric Schroeder, 1963.74

This painting of Asavari Ragini is the last folio of the Ragamala picture book prepared by Jaikisan of Malpura. According to one tradition, this raga is performed around midday during winter. Asavari Ragini is commonly pictorialized as a female snake charmer. Here, we see a lone woman seated on a pink rock playing an archaic flute with eight snakes variously positioned in front of her as if dancing to her tune. The name Asavari refers to a tribal woman ( from śabara referring to the tribal community in the mountains), and her green skirt made of peacock plumes represents this idea. Although bare chested, her body is fully adorned ( i.e. not an ascetic) and conveys the idea of a love-lorn heroine who ascends the mountain top as one version of the text describes her. While the iconography of a female snake charmer is a common repertoire for this raga in surviving Ragamala paintings, other iconographic details and the composition make this painting rather unique, suggesting the artist Jaikisan’s creative interventions that put much emphasis on water.

With her long curly black hair flowing down her back, Asavari looks as if she just came from a bath in the stream flowing under her pink rock. Trailing dark gray strokes directly under her seem to represent the dripping water from her wet body, further suggesting her association with water underneath. The painting’s association with water is further emphasized through the nine snakes: controlling serpentine beings is long associated with controlling water as this visual essay on nagas or serpent beings in the Himalayas illustrates. Painted in lead white and carbon black pigments, the snakes are materially the same as the composition of water depicted in this painting. The rock formations painted in pink that envelope Asavari and her serpentine companions are accentuated further with gentle strokes of organic red that make them look like lotus petals. With the water below, it looks as if the whole central scene is taking place inside a giant lotus blossom floating on water instead of a rocky hill top. In fact, this composition with an upside down U shaped central area surrounded by pink rocks recalls the first painting of the picture book, Bhairava Raga that started with the story of the Descent of Ganga also in this exhibition. Instead of Dancing Shiva-Parvati with the celestial river gushing out to the picture plane as if signaling the arrival of monsoon, the snakes dance while the celestial river flows steadily below during the quieter winter months. The sun is strong, and no peacocks are in sight although their presence is signaled by the peacock feather skirt of Asavari. A snake pays homage to the Shiva linga, the abstract phallic form of Shiva on yoni under a tree above Asavari’s abode, marking his presence. [JK]

Evelyn Rydz

Unraveling

Evelyn Rydz (American, 1979)

2023

Oil pigment color pencils on duralar

Evelyn Rydz. Courtesy Ellen Miller Gallery

Ecocritical art does more than provide explicit visibility of anthropogenic climate change. In her Unraveling series of drawings on duralar, Rydz enables us to sense the long duree of microplastics through the gradual fraying of scrap fishing material in water.

Collecting wave-beaten debris from the New England coastline, Rydz first creates assemblages out of nylon fishing twine, braiding together these loose plastic fibers as fishermen themselves do. Rydz’s resultant line is not a functional repurposing of these non-biodegradable thermoplastics, instead evidence that even its reuse cannot defy its inherent synthetic materiality. Rydz then illustrates these combines in near-hyperrealistic detail, the penciled and vibrant oil pigment colours seemingly suspended on the translucent duralar surface, with neon sapphire blues, teals and emerald greens infracted with flecks of bright tangerine. The reconstituted fishing line is at once tight in its highly interwoven form, yet on the brink of disintegration, with the originally braided lines now untwisted and unable to retain their original tautness and density. While some sections of this line still bear a composed sheen, they soon unravel into helix loops, with mounds of seaweed like furling with no distinguishable start or end, this grafting and fusing of scraps equally as precarious as the knotted sections of the rope. Untethered strands free themselves from the combined rope, Rydz impressing these light and singular marks upon the duralar decisively—indexing a constant state of undoing. It is through registering these individual fragments that we appreciate the granular definition in Rydz’s drawing; each mark forms a fibre, each fibre forms a strand, which then forms a thread, then forms a braid, forming a fishing line. The mark, emblematic of synthetic polymers, is the smallest, indivisible unit, seemingly insignificant yet bearing a lasting impact.

DETAIL ONE

Rydz is also conscious that her composition is but a fragment of the tons of waste that are now forming oceanic garbage patches. By excising this singular frame from much longer combined ropes, Rydz samples segments that metaphorically resemble coastlines, imputing the current state of coasts lined with plastic waste. Rydz instinctual response to found material and the readymade object thus produces an eco-critical visual language that is not obscured by the imperceptible mass of big data, of percentages and predictive statistics. It is rooted in the mundane, yet pervasive aspects of human contributions to climate change. [TW]

Outflux

Evelyn Rydz (American, 1979)

2023

Variable dimensions

Archival pigment prints

Image Courtesy of the artist and Ellen Miller Gallery, photograph by Julia Featheringill.

Any study of the ocean necessitates some level of abstraction, because one cannot neatly demarcate one ocean body from the other. The regulatory body which defines oceanic borders, International Hydrological Organization (originally International Hydrological Bureau) is 102 years old, but it only produced its first document delineating the “Limits of Oceans and Seas” in 1947, under the Special Publication No. 23 (which was most recently revised in its 4th edition in 2002). While modern oceanography has determined the five oceans (Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic, Southern) by their biological, chemical, physical, geological, and paleo/historical definitions, the World Ocean is ultimately a continuous and interdependent body of water, and perhaps needs to be studied on the planetary scale. These bodies of knowledge (and the authorities behind them) are often construed to be avowedly apolitical, meant for pure navigational functionality and scientific exploration of the uncharted. What then is the aesthetic function of figuring an ocean’s limits, if not to convey its sheer mass with some brevity?

With Rydz’s Outflux, growing out of the Open Oceans—together/apart series, the universal 1972 NASA Blue Marble’s impression of the ocean’s seemingly uniform surface is contested by the artist’s highly localized and temporally contingent perspective. Developed from her practice of documenting local water bodies, Outflux is a sculptural collage of printed photographs taken on the New England, Cuban and Colombian coastlines at different times of day. Instead of trying to depict the oceans in their horizontal width, Rydz samples slivers of waves, overlapping these cut outs to form a connective water body that sprawls across the gallery floor. Unlike the vernacular understanding of the ocean’s surface as merely reflective of the sky, the variegated color spectrum in Rydz’s Open Oceans perhaps proves the ocean’s volumetric constitution, the hues of cyan, turquoise, cool grays, and even murky kelp green indexing rich oceanic ecologies. While the sculptural installation appears as a coherent object, the contrast between the ocean surfaces poses the questions of when one ocean fades into the other, and which migratory journeys across these bodies would be able to notice them. [TW]

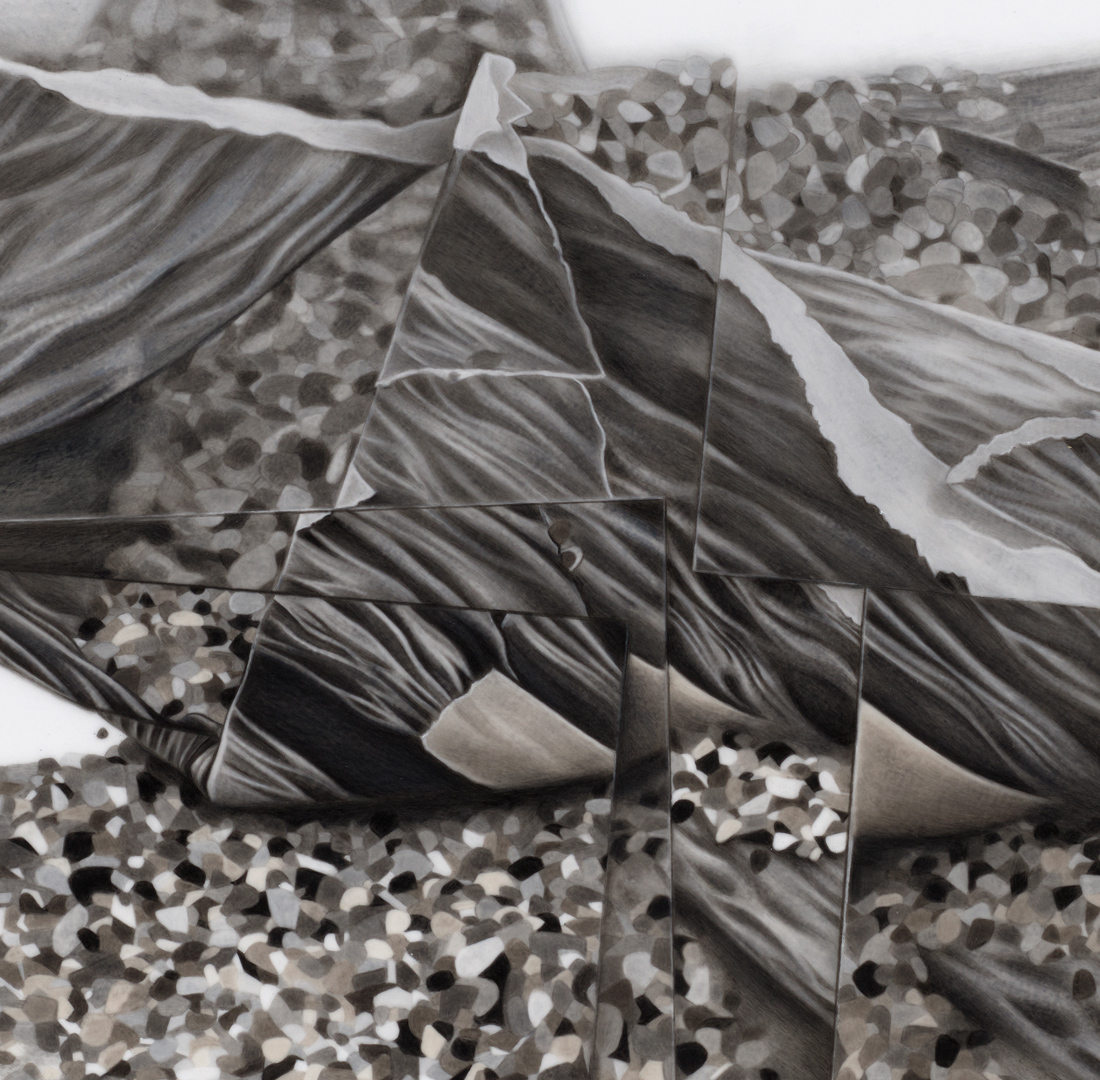

Folded Waters (In Memory of Persistence)

Evelyn Rydz (American, 1979)

2023

20 x 25 ¾ inches

Oil pigment color pencils on duralar

Evelyn Rydz. Courtesy Ellen Miller Gallery

Working with similar photographic captures of ocean surfaces as in Open Oceans- together/apart (2021–), Rydz returns the water surface as photographic print to the water, staging an isolated wave on a pebbled coast. Rydz reanimates the surface by imagining the surface as continually moving, folding the 2-dimensional print to resemble a wave, not quite of Hokusai theatricality but of equal dynamism. There is no specific template or shape of a wave being moulded to; Rydz creases and plies the paper as she intuits multiple waves to crash upon another. Sensing the diffraction of multiple collisions at once, the result is a photographic print wave that spills out across the pebble ground, a physics-mimicry without need of precise calculation. Weighing the folded print down with some wave-beaten stones, the wave is not simply a solitary cascade out in far sea, it is returning and withdrawing from the coast.

Rydz does not stop there, leaving the photographic print-wave as an incidental installation on the coastline. She photographs this momentary formation, and returns to her studio to once again scrutinise water’s form. Printing out this secondary photographic capture, she once again folds the print to isolate the wave, marking its contours. Rydz then relies on her spectacular draftsmanship to vivify water’s material qualities, namely its endless fluidity in silk-like gradations of grays, marked against the decisive cuts at the ends of white paper and the weight imposed by congregations of pebbles. Ryd’z folded waters are anything but flat, the creases from the secondary photographic print registering in the final drawing like the marks on folded cartographic illustrations, this time not indiscriminately measuring the expanse of water but fixating on one specific square inch.

DETAIL ONE

DETAIL TWO

This dual mediation of a simple water is part of Rydz’s ongoing interest in the materiality of water’s surface, namely the property of surface tension in which water particles on the surface shrink to the minus surface area possible. The surface skin of water is always cohering unto itself, a movement that produces its very volumetric or spherical forms (in water droplets) rather than infinitely spreading out. Fixating on this innate latency of water allows us to reconsider the oceans as an empty receptacle for human byproducts and waste. [TW]