FETCHING

WATER

Most residents of cities in temperate climates get their water easily from a tap connected to a managed water system. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas of the Global South, daily access to safe, clean water remains a challenge, with one in four of the world’s population without such access. Fetching water from a public well or open water source in traditional societies was often a women’s chore. Pictured in these historic photographs paired with a painting from India, women are shown carrying jars, mostly filled with water. Collected as souvenirs, these pocket-size photographs portray different types of people, frequently exoticized as a colonial subject. In this exhibition they introduce women’s labor in managing water. Even today, women in the rural areas of the Global South walk for on average three to four miles to fetch water, often barefoot. [JK]

Once or twice on any given day in an Indian village or an urban communal setting, the space around the water supply is swarmed by women. The turn of the pulley over a well, the mechanical screech of the handpump, or the piercing thunder of modern motors, all rhythmically invoke potable waters from the depths of the earth's womb. These waters are collected in round pots of clay, metal and, more recently, repurposed plastic containers of some known and many unknown shapes. Accompanied by the faint tinkling of anklets and glass bangles, and a mellow chatter with an occasional laugh or a chide, this is a daily routine that is evidently gendered.

In South Asian religious imaginations, youthful women carrying pots of water or ambrosia have been a common leitmotif evoking female fecundity and auspiciousness. The woman's body was often likened to the pot, in that her womb was the receptacle and shelter for a young life, and her breasts offered nourishment to the newborn. And perhaps this very association gendered the acts of household obligations as feminine. Even today, remunerative acts associated with water, such as digging wells, cutting canals and bringing filled water tanks to communities is a masculine pursuit, whereas, bringing these waters home for household use continues to be a feminine obligation. Women carrying pots was, and continues to be, a sight symbolic of female occupation and agency limited to the domestic sphere.

In 1840, within a year of its introduction in Europe, Photography was welcomed with much enthusiasm in India. By the mid-1850s amateur photographic societies had been established in Madras, Bombay and Bengal, coinciding with an increased interest in ethnological studies that supplemented European colonial expansions. The Bombay Photographic Society began to produce portraits of Indian castes and occupations as early as 1856. Amateur photographers were soon to give in to this trend that continued for the rest of the century and beyond.

The photographs in this exhibition were taken in this context, likely between 1860-1899. Three of these– H|AM P1982.329.27; H|AM P1982.329.37; and H|AM P1982.329.14– are carte de visites, or visiting cards that were traded from 1860 onwards among friends and visitors in urban European settings. Usually portraying images of elite and individuals of celebrity fame, portraits of ethnographic studies, like these images of women, are rarely seen on carte de visites. [RA]

Artist once known

Untitled (young woman balancing pots on head) carte-de-visite

Artist Once Known

1860 – 1899

4 x 2 ½ inches

Albumen silver print on card

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Purchase through the generosity of Melvin R. Seiden, P1982.329.27

This photograph likely depicts a woman from today’s Maharashtra in western Deccan. The woven patterns on her blouse, the drapery of her sari and her nosepin– all support this identification. She balances two brass pots on her head and holds a smaller one in her pendent right hand. Her jewelry, clothes and pots indicate that she hailed from a reasonably well-to-do family. The wooden balustrade and the plain screen behind her suggest a studio setting where she may have been requested to pose for the photographer. [RA]

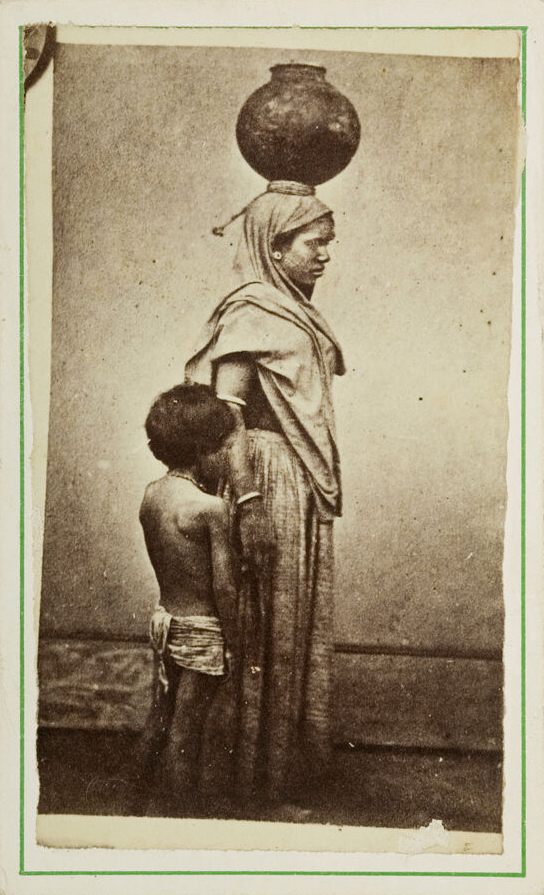

Untitled (woman standing with pot balanced on top of head,

young boy with back to camera standing next to her) carte-de-visite

Artist Once Known

1860 – 1899

4 x 2 ½ inches

Albumen silver print on card

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Purchase through the generosity of Melvin R. Seiden, P1982.329.14

A woman stands in profile with a young boy who faces away from the camera. She balances an earthen pot on her head with her left hand, and with her right hand holds the hand of the boy, likely her own son. She wears a pleated skirt and a shawl that runs across her chest from behind her right shoulder. An armlet and a bangle can be seen on her pendent right arm. These sartorial features suggest that she is from western India. The young boy wears only a loin cloth around his waist. Their soiled clothing suggests their impoverished state. [RA]

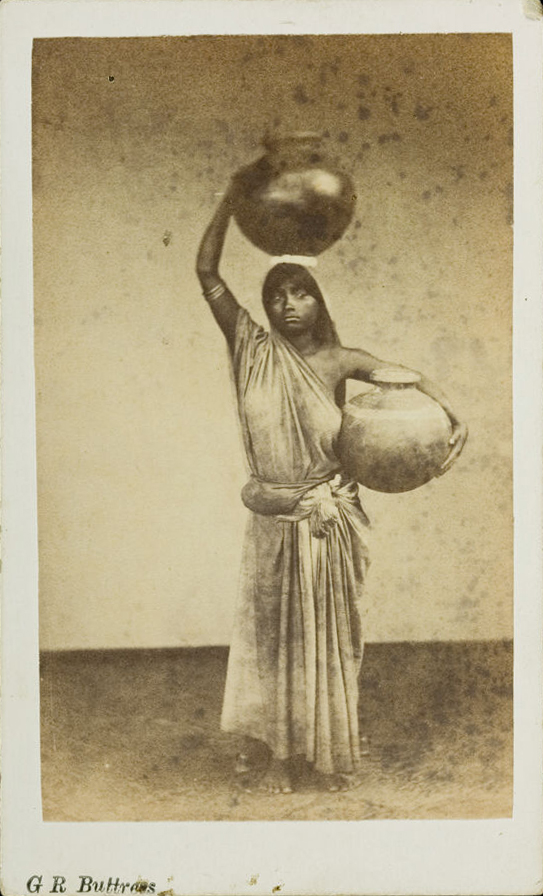

Untitled (woman carrying two earthen water pots) carte-de-visite

Artist Once Known

1860 – 1899

4 x 2 ½ inches

Albumen silver print on card

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Purchase through the generosity of Melvin R. Seiden, P1982.329.37

An impoverished woman poses with her two clay pots typically used for carrying water. She balances one pot on her head and the other on her waist. Her only piece of jewelry are the plain silver armlets that she wears in her right arm. A piece of cloth tied around her waist acts as a bag for her small belongings. Her sari draped across her chest from behind her right shoulder suggests that she hailed from western India. The inscription on the bottom, “G R Buttress” could indicate the name of the photographer or the printer or patron of this carte de visite. A handwritten inscription on the back reads, “Woman carrying water chatties”, chattie being the anglicized Tamil word caṭṭi, meaning earthen pot. This latter inscription suggests that this carte de visite may have traveled across the subcontinent or exchanged hands with someone who had been versed in Tamil. [RA]

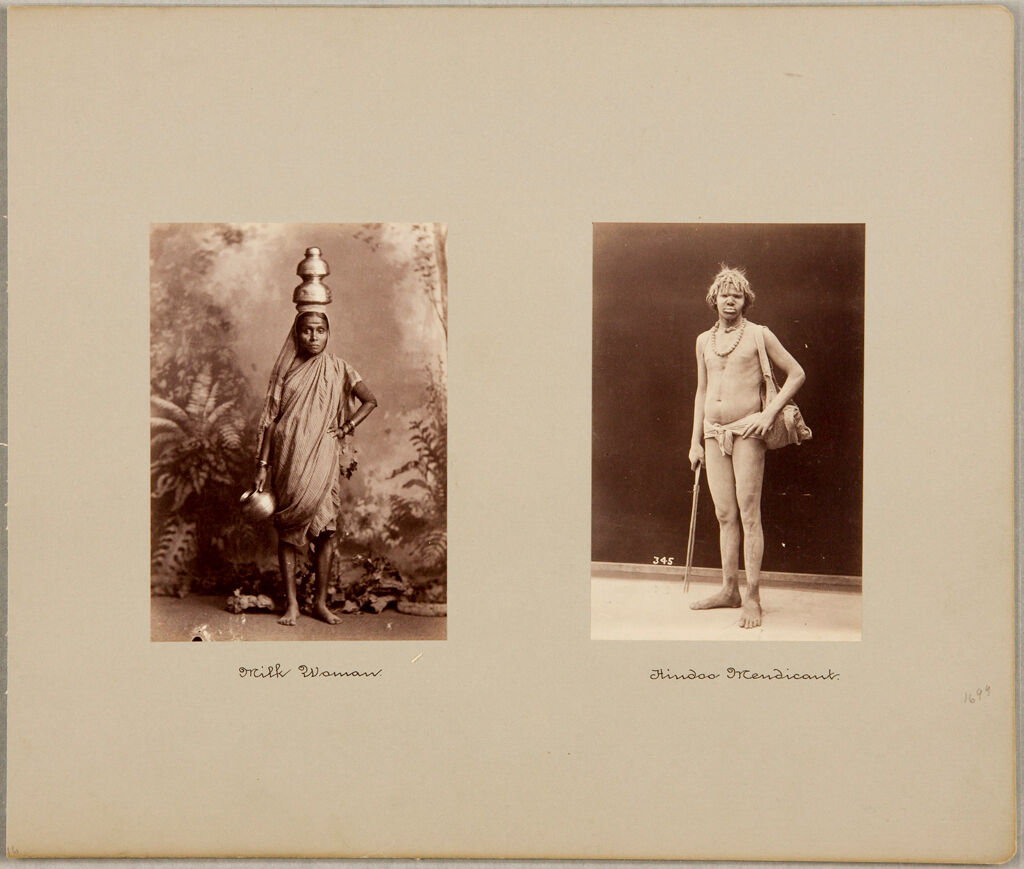

Milk Woman

Artist Once Known

c.1880

5 ½ x 3 ⅞ inches

mount: 11 x 13 inches

Albumen silver print

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Janet and Daniel Tassel, 2007.219.47.1

This Albumen silver print-photograph depicts a senior woman likely from Maharashtra, as may be evinced from the drapery style of her sari and the red horizontal stripe of kumkuma across her forehead. She balances two brass pots on her head, topped by an up-turned smaller pot of serving size. She holds another brass pot in her pendent right hand and rests the left hand on her waist. An inscription below this photograph identifies her as a “milk woman” and recalls the famous oil painting by Raja Ravi Varma titled, the Milkmaid (1904). There too one sees a Maharashtran woman coyly balancing two brass pots in her left hand.

This photograph shares a mount with a photograph of an ash-smeared mendicant, who wears only a loin cloth around his waist. A small cloth-bag hangs from his left shoulder and an unidentified instrument, possibly a long tambourine, is held in his right hand. He wears a string of rosaries and a whistle in a smaller necklace that confirms his sectarian identity as a Nath Yogi. [RA]

Woman Balancing a Gold Jug on her Head (painting, recto; text, verso)

Artist once known from Rajasthan, India

c.1800

7 x 4 ⅝ inches

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of John Kenneth Galbraith, 1972.359

At once, a young maiden turns around as though she were interrupted from her onward journey. Her body twists, revealing the slender waist rising from her wide hips, much like the shape of the golden pot she balances on her head. In her swift motion, the pleats of her onion-pink skirt unfurl and a festoon of pearls dangles behind her head. Given the elaborate decorations on the pot, it is less likely for it to be an ordinary container of water or milk and for the maiden to be an ordinary woman. Adorned in fineries, she may be likened to a celestial being. One is reminded of the river goddesses who similarly carry waters of their rivers in beautiful golden pots as seen in the painting of the goddess Ganga in the next section (See H|AM 1997.236). Far across the pistachio green landscape, is a curved line of scalloped clouds that add dimension to her inhabited space. The inscription on the top, though readable, remains to be understood, but a young woman’s association with the water pot is, no doubt, an old marker of fecundity and auspiciousness. [RA]

Brass Lotas (Water Pots)

Brass Lota (Water Pot), India, 20th century

Miniature Clay Pot, India, 2022

Jinah Kim Collection

Resting on a narrow base with a spherical body, the pot in Indic imaginations is believed to contain inexhaustible plenitude that overflows from its wide opening at the top. Its spherical shape recalls the all-containing cosmic egg and the life-nourishing womb of the mother. Thus auspicious, the purna ghata (full-orbed pot) variously called kalasa and kumbha in Sanskrit, is often found in ritual settings for containing ablutionary waters and divine spirits, and in sacred architecture as emblems of limitless fortunes. Resembling the golden pots described in sacred scriptures, brass pots such as these are a commonplace in South Asian households for religious and domestic use. Pilgrims traveling long distances carry the waters of sacred rivers and lakes in similar pots that are often sealed with a thin metal sheet or a screw cap. As an iconographic feature, these may be found in the images of ascetic figures and river goddesses that carry their waters in golden pots as seen in the next section. Here, these pots are placed alongside a miniature pot of clay called matka or kulhad in Hindi, in which beverages and desserts are served throughout the streets of northern South Asia. Besides their form and function, metal and clay pots also share an important feature of their materiality—they both may be endlessly recycled and given newer forms. The brass pots, colloquially called lota in Hindi were bought by curator Jinah Kim in the holy city of Banaras, where new and old pots are sold in countless stores across the city’s narrow winding streets. A staple throughout her journey in north and east India was beverages served in miniature clay pots similar to the one displayed here that would be broken after a single use. [RA]