Water Stories: Cultivating Climate Empathy through Art

"In the end, stories are what’s left of us

we are no more than the few tales that persist.”

— Rushdie, 1995, 11

"In the beginning this world was just water"

— Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Upaniṣad, 5,5

Introduction: Water and Stories

Amitav Ghosh tells two personal stories of extreme weather events in his introduction to The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016). The first one is the story of his ancestors, whose village on the shore of the Padma River in today’s Bangladesh was completely wiped out by the river when it changed the course suddenly in the mid 1850-s. The second one is a recollection of his own, when he nearly missed being swept up by a powerful tornado “about 50 meters wide” in Delhi on March 17,1978. The story of a mighty river changing her course overnight and swallowing a whole village may seem improbable, like a myth, but, this kind of event –a body of water destroying a human settlement—appears in our news feed with menacing regularity in the age of climate change.

One such disaster is the 2022 Pakistan flooding. As the BBC reported subsequently, “Pakistan contributes less than 1% of the global greenhouse gasses that warm our planet, but its geography makes it extremely vulnerable to climate change.” It is not just geography, but economic disparity and political instability caused by a global power imbalance that compounds the impact of climate disasters in the Global South, where all the top ten deadliest natural disasters of 2022 occurred.

Despite abundant scientific reports on the causes of climate change, and even more plentiful reporting on the loss of human life and material resources related to the climate-crisis, it is difficult to fully comprehend the negative impacts of anthropogenic climate change beyond the theoretical level. The beyond-human scale of this phenomenon challenges our capacity to make sense of its deep and abiding consequences, especially when these disastrous climate events unfold in regions outside one’s own. Reading the news of the aftermath of devastating flooding in Sindh, Pakistan, while sitting in the temperate climate of Cambridge, MA makes one feel guilty perhaps, but the immense physical distance from this event gives the reader a false sense of security; one becomes disassociated from these climate disasters and their effects. How can a reader sympathize with and understand the precarious situation where no clean water is available amidst so much flood water everywhere, when they get clean, drinkable water from the tap at any time?

Here we invoke the transformative power of stories, old or new, individual or collective, in cultivating empathy; a human quality much needed in formulating equitable and wise approaches to the consequences of climate change, which affect the economically disadvantaged areas of the globe the most, especially the former colonies of western imperial powers in the Global South. More than any statistics, diagrams, and charts, it is the stories shared across different communities and cultures that can shift perspectives and recalibrate our relationships with nature from an extractive economy to one of respect and compassion. Stories of nature-human relationships from the Global South and indigenous communities everywhere will be particularly important.

The impact of climate change is felt and measured most intimately through our experience of water, whether in drought or flooding, or securing safe drinking water. It is no wonder that the climate crisis is often called a water crisis. As the most visceral and primal element of life on this planet, not just of humans, water connects us all. Yet what water means to us is culturally specific, and a person’s relationship with water in a city is vastly different from that in a rural area. The exhibition “Water Stories” presents works that tell alternate stories of water experience that treat water not as a commodity and resource to exploit but as a cyclical, life-giving, life-dissolving, inert but innately alive, spiritual force; a notion that is shared widely among indigenous communities, particularly in the Global South. By juxtaposing older, traditional paintings that depict mythological stories with works by contemporary artists that evoke different aesthetic experiences of water in the age of climate crisis, “Water Stories” encourages viewers to appreciate water’s multivalent meaning and to contemplate their own relationship with water. When viewed through the lens of ecology and climate change, a mythological story about a celestial river saving the ancestors of an ancient sage can resonate with the reverence and respect required to recalibrate human relationships with the environment today. In this essay, I share a few stories and art works that inspired this exhibition.

Sunrise over the Ganga River at the Assi ghat, Varanasi, January 2013. Photo © Jinah Kim

Story 1 — Ganga, A River Goddess

One recent study published in the Earth’s Future (American Geophysics Union) suggests that the extreme precipitation that led to the devastating flood in Pakistan in August 2022 was “caused by two atmospheric rivers.” According to the American Meteorological Society’s glossary, atmospheric rivers are that rivers of water vapor, which comprise the “largest ‘rivers’ of fresh water on Earth, transporting on average more than double the flow of the Amazon River.” The atmospheric rivers that cause floods on Earth today find an uncanny resonance in the story of the descent of the celestial river, Ganga (Anglicized as Ganges) in Hindu mythology.

Ganga is one of the major holy rivers of India and is considered by many to be the holiest of all: its water is often required in major Hindu rituals and for rites of passage. Many rulers of the past tried to harness the sacral power of this river for political gain and, even today, dying by Ganga and having one’s cremated ashes flow into the river are highly desirable and pious acts in death rituals among Hindu communities. As a physical river, Ganga originates in the Himalayas at Gangotri, lit. “place where Ganga rises”, in Uttarakhand, India where the river is called Bhagirathi. The Ganga then flows through the plains of Northern India (aptly named Gangetic Plains after the anglicized name of the river) and exits into the Bay of Bengal ( at the Gangetic Delta.1 In Indic mythology, this mighty river was once a celestial river residing in the heavenly realms. Several stories explain how this celestial river became an earthly one as explained in the essay by Raghunath Akarsh. In one popular version of this story, Ganga, a river goddess, came down to Earth through the mediation of lord Shiva, one of the major Hindu gods, to help with an ancestral rite.2

This story begins with a just and mighty king named Sagara whose 60,000 sons destroy the Earth in search of a sacrificial horse, not unlike human activities over the past two centuries, which has wrought havoc in the environment and led to the present climate crisis. Sagara’s sons were cursed and burned to ashes due to the disturbances they caused. A royal sage named Bhagiratha was determined to save his ancestors and perform the proper rites for their liberation, which required their ashes to be dissolved away by the waters of Ganga. According to a version in Valmiki’s Ramayana (lit. “adventures of Rama”, one of the human avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu), Bhagiratha undertook an extreme penance lasting a thousand years, eventually gaining the boon of having the celestial river, Ganga, come down to Earth to wash away the ashes of his ancestors.3 Bhagiratha’s wish was granted by the god Brahma who advised him to seek help from the god Shiva who resides on Mount Kailash in the high Himalayas (identified as the mountain peak in the Ngari prefecture, Tibetan Autonomous Region) to break the fall of the mighty celestial river. He took another extreme penance, this time standing on one big toe for one year. Impressed by Bhagiratha’s austerity, Shiva agrees to allow Ganga to fall on his head thus making the haughty river goddess meander through his tall, matted locks of hair, just as the streams of the Ganga River pass through the numerous gorges and valleys of the Himalayan mountain range. This story mythologizes the natural phenomenon of a Himalayan River system, layering gendered religious significance on to the environment.

The story of the descent of Ganga was a popular subject in art and was depicted in royally sponsored monuments in pre-colonial South Asia, suggesting the political and cultural importance of managing and controlling water: just as Shiva intervened to break the fall of the celestial river to save the Earth, a successful ruler was to irrigate and manage the water to benefit the land and its people.4

Shiva receiving the Ganges in his locks, cave shrine, Tiruchirapalli (Trichy), during the reign of Pallava king Mahendra, c.600-30

Shiva receiving Ganges on his hair lock (Gangādharamūrti), left side wall of the entrance to the main shrine, Kailāsa temple, Ellora, c.757-83

In many early representations, Ganga is customarily represented as a two-armed goddess paying homage to Shiva and landing on a lock of his hair. In much later paintings like the eighteenth century Bhairava Raga painting in this exhibition, the episode is referred to by a stream of water that shoots out from Shiva’s matted locks of hair. In another ingenious example built during the seventh century under the Pallava dynasty in the ancient port town of Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu, India, the Pallava artists represented the story on the surface of giant boulders, harnessing nature and the ecological calendar to amplify the political and spiritual significance of water.

Carved on two adjoining granite boulders with a cleft in the middle, this sculpted relief is located just under half a mile (800m) from the shore, facing due east overlooking the Bay of Bengal. Measuring about 83 by 38 feet (25 x 12 meters), this is one of the largest outdoor relief sculptures in the world, and probably one of the earliest ecological art works. It represents multiple stories at once, including the parody of a cat performing a penance, which appears on the lower right-hand corner of the cleft in the center of the two boulders – the space which forms a water channel during the monsoon.5

Penance of a fat cat

Sculpted cliff

Above this cleft comprised a man-made cistern that harvested water during the rainy season, allowing it to cascade down to the pool below, literally enacting the descent of the celestial river, here rainwater, made possible by the intervention of the Pallava king Narasimhavarman (I) according to a seasonal calendar. On the lower left side, the quotidian activities of a riverbank unfold: morning rituals such as the sun salute, bathing (suggested by the action of squeezing hair) and collecting water in a jar; all while ascetics engage in religious activities in front of a Vishnu temple by the river. Further up on the boulder an emaciated ascetic stands in “tree pose” and four-armed Shiva grants a boon. The Descent of Ganga or the cascading monsoon water in the middle of this relief sculpture is further animated by the nagas, semi-divine serpentine beings in Indic mythology, rising upwards in a row. The naga king with a seven-headed hood leads the way, holding his hands in veneration (anjali mudra) and is followed by his consort, a nagini, also in anjali mudra. Below her, a single-hooded snake is depicted in the narrowest part of the cleft, ensuring the serpentine reference is clearly conveyed. Imagine water gushing down from above as the nagas jump up in celebration and celestial and sentient beings alike arrive to celebrate this occasion from all sides. Although no text specifies the nagas are the first to welcome the Ganga’s descent, nagas are autochthonous semi-divine beings crucial in controlling and managing water in Indic belief systems as suggested in the essay by Victoria Andrews.

Story 2 — A Clay Water Pot

Representing water in art, especially in visual art, presents a challenge. In pre-colonial South Asia where a strong, prevailing inclination was for figurative representation, one of the long-lasting artistic interventions was to signal the presence of water through the iconography of the water container, like a round and rimmed water pot (like lota), like those seen in the historic photographs in this exhibition. This iconographic feature is seen consistently in images of the river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna who are often found adorning the main portals to temple spaces in South Asia.

Ganga on makara (left) & Yamuna on Turtle (Right), Ahichchhatra, U.P, Gupta period, c.5th century CE, Terracotta, National Museum, New Delhi

Doorway to the main sanctum, Khichakesvari temple, Kiching, Odisha.

Doorway to the main sanctum, Khichakesvari temple, Kiching, Odisha. (close-up)

Yamuna, door portal (left), Ganga, door portal (right), Khichakesvari temple, Kiching, Odisha, ca. 11th century

In an early terracotta image now in the National Museum, New Delhi, the goddess Ganga carries a round water pot in her raised left hand. She casually stands on her vehicle, a makara (mythical aquatic creature) while an attendant holds an umbrella over her. Images like this flanked the portal to the main sanctum of a temple along with an image of the goddess Yamuna who is similarly represented as a female figure carrying a pot, but riding her vehicle, a tortoise. M.F. Husain’s Ganga-Yamuna in this exhibition builds on this enduring tradition of pairing these two river goddesses, who personify the sacred rivers that originate in the Himalayas and meet at a confluence known as Sangam in today’s Prayagraj (also known as Allahabad), Uttar Pradesh, which is considered one of the most auspicious pilgrimage sites and a desirable spot for the performance of ancestral rites like Pind Daan ( piṇḍa dāna, the offering of rice balls to the deceased) among Hindu communities.

View from Yamuna and Ganga’s confluence, Sangam, Prayagraj ( Allahabad), January 4 2023. Photo © Jinah Kim

A water pot may also be the conduit for a budding romance, as seen in the eighteenth-century painting from Kishangarh on display at the Harvard Art Museums (1927.350 until October 17, 2023). A maiden holds a fine water pot and offers water to an admirer on a blue horse.

A Prince Receives a Water Jug from a Young Woman at a Well, c. 1745 CE, Kishangarh, Rajasthan, Harvard Art Museums 1972.350

The intensity in the exchange of gazes – the man looks up to her intently while the woman holds her eyes slightly down cast but towards him – is further amplified by the clever rendering of their hands: the lady’s right hand and the rider’s left hand hug the water pot while the other hands form mirrored gestures. This intentional choreography is further displayed in the portrayal of the female companions – one of whom glances at the exchange with envy while the other three are engaged in conversation, or gossip, perhaps, indicated by the raised gesture of the woman in pink skirt. The setting of this nascent romance is not bucolic: the dark sky suggests a gathering monsoon storm. Against this spirited and verdant backdrop, a handsomely constructed white water well stands out; four maidens are seen drawing its water effortlessly and collect it into the four pots that are lined up along a perforated parapet wall, demonstrating a common method of water management and distribution in pre-modern South Asia. Any excess water, including rainwater, would drain through the channel seen in the side of the platform and flow into a small stream. Compositionally, this stream is in fact the center of the pictorial space. In a way, the painting is as much about the budding romance and the sociality around a well – a romantic theme known as the panagatha (paṇaghatha līlā, the play at the steps of water) – as it is about water: the system of harvesting ground water at the center of this painting and the water of the heavy monsoon clouds in the sky above, the turbulent water of a lake in the background, and the green water embedded in the land.6

Detail from A Prince Receives a Water Jug from a Young Woman at a Well

Detail from A Prince Receives a Water Jug from a Young Woman at a Well

A humble clay pot takes center stage in one of the most popular love stories of Punjab and Sindh regions of Pakistan. The tragic love story of Sohni-Mahiwal unfolds on the banks of the Chenab River, which originates in the western Himalayas and flows through India and Pakistan. Sohni was a daughter of an earthen pot maker and lived in a village near the Chenab River in the Punjab. As she grew up, she mastered the art of painting clay pots and helped her father with his shop. One day, a young prince from Central Asia named Mirza Izzat Beg who was traveling with a merchant caravan, visited the shop and fell in love with Sohni. He abandoned the caravan to stay near her. Not knowing his feelings for Sohni, her father hired Izzat Beg as a water buffalo herder, thus earning him the name “Mahiwal (or Mahinval)” (lit. water buffalo specialist; see water buffalo herding in the fragile ecosystem of Southern Iraq’s Marshland in Alia Farid’s Chibayisi in this exhibition).7 Tragedy begins when the family arranged Sohni’s marriage to the son of another potter family. Yearning to see Sohni, Mahiwal herded his buffalos on to the riverbank opposite Sohni’s marital home. Sohni, in turn, braved the strong currents of the Chenab River, swimming across this river at night to meet Mahiwal in secret, using her clay pot as a float. Upon discovering the secret affair one day, her sister-in-law switched Sohni’s trusted clay pot with another of unfired clay. As Sohni crossed the river that night, the unfired clay pot began to soften and disintegrate. As Sohni struggled to make it to the other shore, hanging on to a melting pot, Mahiwal jumped into the water to save his beloved – the mighty Chenab River swallowed them both.

Sohni swims across the Chenab River to meet Mahiwal, c.1770s (before 1774), Awadh ( Lucknow or Farrukhabad), British Museum 1974,0617,0.10.45

This sad folk story has remained immensely popular since the turn of the eighteenth century when a Sindhi version was penned down by the Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689/1690-1752). An eighteenth-century painting from the kingdom of Awadh (Uttar Pradesh, India) now in the British Museum depicts the story poignantly: Sohni is shown swimming across the river holding on to a clay pot in the dark. Only the river and our protagonists seem to be lit up in the picture. While Sohni stretches her right arm as if reaching for the shore, Mahiwal plays his flute to calm the water buffalos into sleep, unaware of Sohni’s struggle. The painting seems to emphasize Sohni’s quest for love rather than the tragic ending, but the futility of this quest is signaled by an ascetic who sits with his eyes closed in front of a cave-like setting at the bottom left corner of the painting. He sits on an antelope skin with his legs tied with a strap (i.e. a yogapaṭṭa) and has a long piped hookah in his mouth, bearing the common accoutrements seen in portraits of both Muslim (especially Sufi) and Hindu ascetics or yogis/jogis.8 He probably holds a string of prayer beads in the left hand that is covered by a long sleeve as he sits quietly chanting by the small fire. Sufi poets like Bhittai harnessed folk love stories to express the soul’s quest for the divine love, and the ascetic, probably channeling a Sufi jogi, in the corner of the diagonal composition seems to signal the story’s higher spiritual meaning: the unbaked clay pot is an unfit spiritual guide and the river is the “longing for the divine love”.9 Although slightly hidden under Sohni’s clutching left arm, the earthen pot in fact sits at the almost dead center of the composition.

The haunting love story set around this river has inspired many artistic expressions including popular songs and films. The unbaked clay pot is a protagonist in a mesmerizing song from Pakistan titled Paar Chanaa De (Across the Chenab River) which was released in 2016 on Coke Studio (Season 9, episode 4, music by Shilpa Rao and Pakistani rock band Noori). The song turns this story into a dialogue between Sohni and the clay pot, The pot begs Sohni to not go, telling her, “I am a pot made of unbaked clay, bound to melt away in the river. Being unsound and unsteady, I cannot but fail in carrying you across.”10 Here, too, the spiritual message of seeking the right guidance is implicit in these lyrics, which ends in an uplifting climax with the verse “Hold firmly to the sound guide who will take you safely to the shore.”

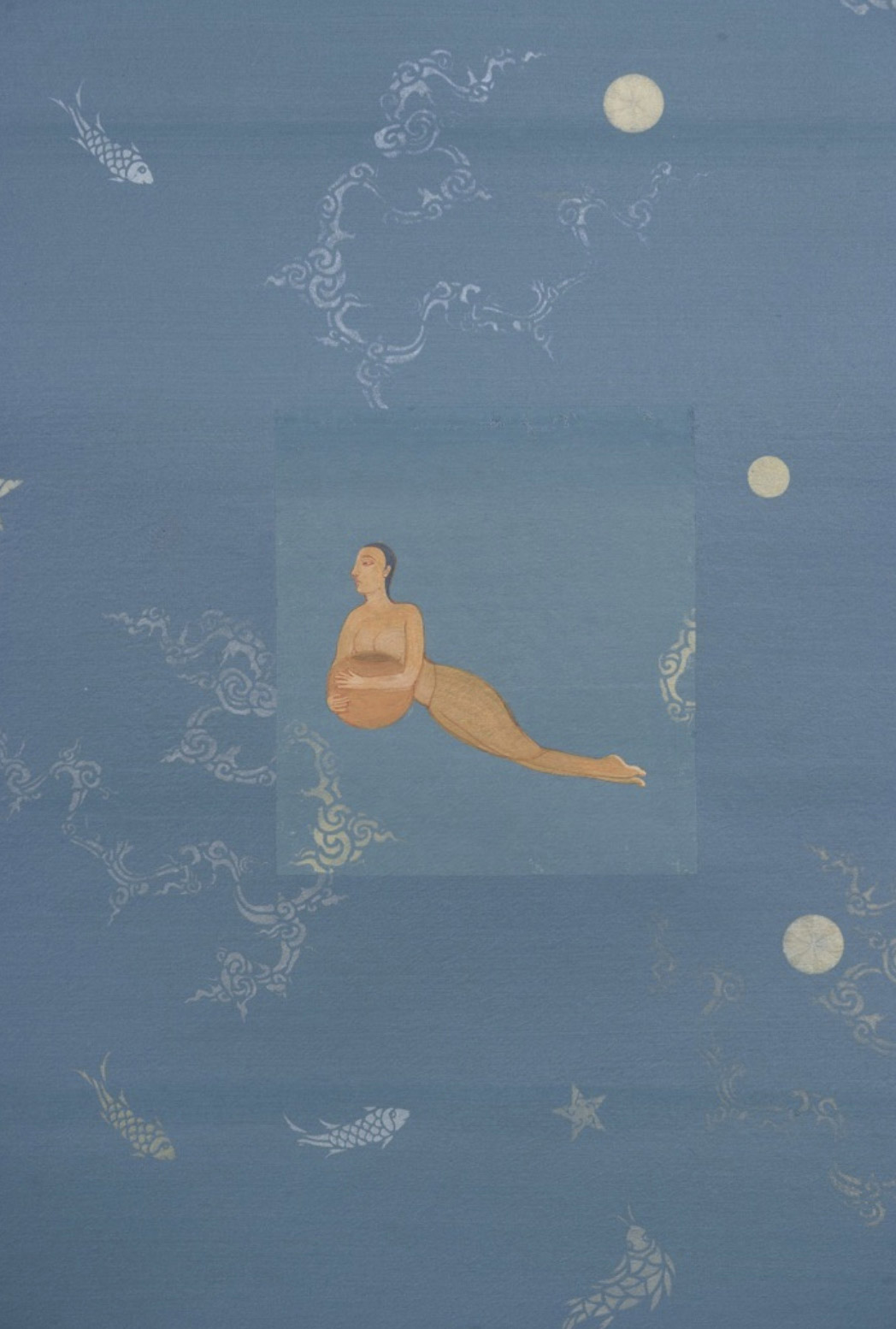

The contemporary artist Nilima Sheikh (b. 1945, India) makes the clay water pot even more prominent in her lyrical painting of this tragic love story titled Chenab 5 (2016-17). Against the expansive blue backdrop of water, Sohni’s body floats over a round clay pot painted in the same brownish hue. Round bubbles and stars among the gently stenciled renderings of fish and swirling waves relate the heartbreaking fate that awaits Sohni who seems to swim so effortlessly. In a way, Sheikh turned Sohni into an eternal figure floating in the ocean, no longer stretching out her hand for her beloved but contently holding on to her clay pot.

Detail from Chenab 5 Nilima Sheikh (b. 1945, India), 2015-16, reproduced by the kind permission of the artist © Nilima Sheikh

Story 3 — Color of Water

What color is water? The most common color used to indicate a body of water is blue, as seen in a virtual map like Google Maps. Blue is used to indicate water by association, rather than being based on any intrinsic color value of the liquid. Anyone who has tried to share the color of water that they had seen would relate to the difficulty of representing water. In Walden (1854)where we find the convergence of the Ganga and the Walden Pond, the American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) labors to explain the color of the Walden Pond in Concord, MA: “…Walden is blue at one time and green at another, even from the same point of view. Lying between the earth and the heavens, it partakes of the color of both. Viewed from a hill-top it reflects the color of the sky; but near at hand it is of a yellowish tint next the shore where you can see the sand, then a light green, which gradually deepens to a uniform dark green in the body of the pond. In some lights, …it is of a vivid green next the shore… I have discerned a matchless and indescribable light blue … more cerulean than the sky itself, alternating with the original dark green on the opposite sides of the waves… It is a vitreous greenish blue, as I remember it, like those patches of the winter sky seen through cloud vistas in the west before sundown….”11 The color of Walden Pond here seems almost chimerical. Thoreau evokes a lot of associated imagery to convey the sense of the color as he experienced it, but what this color means exactly remains elusive and subjective. Artists, especially painters, help shape the way the color of water is seen and understood in any given period.

The reflective nature of water—its tendency to appear in different hues—led artists serving Islamic courts in the early modern period to turn to silver to represent water in painting, as seen in several works in the Harvard Art Museums. A late sixteenth century painting, Sufis by a mountain spring, which was made in the Safavid court at Isfahan, Iran (on display until October 17, 2023) is a good example. The dark gray channel that runs horizontally across the middle of this painting with the patches of green on either side represents the flowing water of a stream. The silver that was used to represent the glinting surface of this stream now appears almost black due to tarnishing. The eighteenth-century Indian painter Jaikisan whose painted folios are featured in this exhibition represented water as grey, using a mixture of lead white pigment with carbon black, according to an analytical study conducted at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies.12

Sufis by a Mountain Spring, c.1590, Isfahan, Safavid period, H|AM 1936.28

The decision to paint water light grey was not, in this case, due to the lack of access to precious metals. In Jaikisan’s painting of Khambhavati Ragini, for instance, there is abundant use of gold and silver: the standing maiden’s shimmery skirt is painted in silver, which has tarnished somewhat, and all the jewelry, decorative details, sun, and even the framing border are painted in shell gold. The text on each folio of Jaikisan’s picture book is, in fact, written with alternating lines of gold and silver. These silver letters were first written in lead white on top of which silver is applied, perhaps ensuring the letters stand out. While gold and silver were readily available, the artist chose to use the more basic pigments (lead white and carbon black) to depict water, a painterly convention that was common in North Indian courtly circles at the time.

The artist once known in Jaipur, Rajasthan who painted the image of the Goddess Ganga in the early nineteenth century (1826 CE) in this exhibition made use of newly available synthetic pigments such as Prussian Blue (also called Berlin Blue) and Emerald Green in addition to precious metals such as gold. According to the Harvard Art Museums’ conservation scientist Katherine Eremin, a combination of Prussian Blue, ultramarine, and lead white was used for coloring the light blue water under the goddess. The subtle blue color of the water in this case may not seem particularly special against other brilliant colors and the gold used in this painting, but the use of three pigments, including precious ultramarine (prepared from the gemstone lapis lazuli), suggests a particular care was taken in rendering the body of water, making it more meaningful.

Khambhavati Ragini

Goddess Ganga

Another early nineteenth century painting from Jodhpur, Rajasthan at the Harvard Art Museums (on view from October 18 2023) used tin for depicting the water of the Yamuna River: on the banks of which the men and women of Vrindavan engage in water play. In another early nineteenth century painting from Kangra in the Himalayan foothills (also on view alongside with the former) a small amount of silver was applied over lead white to depict the same river, the Yamuna.

The Yamuna is perhaps the most frequently portrayed river among the paintings depicting Hindu mythology since the childhood adventures of Krishna, one of the human avatars of Hindu god Vishnu unfolds along the Yamuna River and this story has inspired numerous artistic projects including manuscripts and picture books. The riverscape is often placed at the bottom of the pictorial space as seen in two examples above. In the early sixteenth century, paintings depicting events from the tenth book of the Bhagavata Purana (“Old tales of the lord”, a Vaishnva scripture), which narrates the stories of Krishna’s youth, artists serving Vaishnava communities in the area around Mathura rendered the river in various shades of green, using indigo and orpiment with undulating lines in clay white, as seen in the painting in the Harvard Art Museums collection. (1974.124). (See the pigment analysis data here.)

The Cowgirls Attend Krishna (painting, recto; text, verso), folio from a Bhagavata Purana series, c. 1540, Mathura region, H|AM 1974.124

The Yamuna River is central to the contemporary Indian artist Atul Bhalla’s artistic practice, too. His work in this exhibition shows the artist slowly submerging himself in the water: in fourteen serial photographs, Bhalla’s profile slowly disappears into the water, as if becoming one with Yamuna. It is difficult to describe the color of water in Bhalla’s work as it appears nearly ethereal: tinged with slightly greenish, yellow or light brown hue, Yamuna’s water seamlessly permeates the out of focus backdrop of the riverside scape and sky. The only color that is truly noticeable in the water is that of Bhalla’s reflection.13 Bhalla’s choice of face mounting the photographs on the plexiglass amplifies the sense that we are directly looking at the body of water with a reflective surface. This alluring work invites the viewer to be part of the ritual act of submersion – being one with water – to purify, to renew, and to restore our intimate relationship with the environment, which is impossible to achieve without genuine commitment and conscious efforts to keep the waters clean and clear.

Different colors of water make up the body of Outflux (2023), a site-specific paper sculpture by the contemporary American artist Evelyn Rydz. Variegated hues of green, blue, gray, white in various shades cascade down to the floor carrying memories of different oceans and coasts. Walking around Open Oceans, one may look for and recall the color of the ocean water in her own memory. How blue, how green, how murky, or how shiny was the water? These varied hues are in fact torn paper fragments: the printouts of digital photographs of diverse bodies of waters. Each photograph captures the water’s surface from every ocean that Rydz has visited with the clear intention of connecting all coastlines of the Americas through her art. As noted in Thoreau’s description of the Walden Pond above, the color of water appears different even when viewed from the same location – its permutations depend on the time of day and climatic conditions. By fragmenting the pictures of ocean water from every coastal point that she visited and by mending them together to form a new physical sculpture representing water in its totality, Rydz tells a story of interconnectivity that water generates: water connects all coasts, and, in a way, at a more personal level, helps her trace her genealogy – Rydz identifies herself as “a first-generation American artist with parents born in Cuba and Columbia, and grandparents who escaped Poland during WW II”.14 There may be multiple oceans identified on the globe by geographical convention, but the waters of these distinct oceans, ultimately, flow together crossing socially and politically determined boundaries. Reckoning an ocean’s agency in connecting coasts rather than separating them by unpassable distance compels Rydz to continue documenting open waters and to find their relationships, crafting new stories of human-nature relationship.15

Epilogue

The theme of the sixth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit in 2023 (Feb 3-11, 2023, Shilpakala Academy, Dhaka, Bangladesh) was Bonna (বন্যা), a Bangla or Bengali word for flood. As a feminine noun, the word Bonna is also used as a common given name for girls in Bangladesh. According to the DAS 2023 organizers (chief curator Diana Campbell), while the term “flood” more commonly evokes images of disaster and tragedy, the Bengali word, Bonna, challenges this singular connotation. In a region where water-related extreme weather events have shaped the culture and the ecological calendar for millennia, a flood is not merely a disaster but also an opportunity for regeneration. “Bonna” a video recording of a puppet show made by village children of Thakurgaon in northwestern Bangladesh (at the Gidree Bawlee Foundation) for DAS 2023 and World Weather Network tells a simple story of a community managing to live with extreme weather (drought and flood): people perform rain rituals and anticipate the arrival of the monsoonal clouds that bring Bonna. In this imagination, Bonna is represented as a female character who appears at once wild and caring, with long loose strands of hair made of jute fibers and ropes, and with big eyes made of green leaves. Bonna is the title character, she is the largest of the puppets and she appears at last to every creature’s delight, but people must migrate to higher grounds for her to be able to do the job. When she dances around the rice plant, the plant tells her that it fears for its survival under a potential deluge. Bonna then assures the plant that it will be okay and bids her farewell, promising to return to see her friends next year.

By invoking Bonna, a weather phenomenon which is gendered female, DAS 2023 delves into the issue of gender in climate change and acknowledges that much of this phenomenon has a disproportionate impact on women as Diana Campbell articulates in an interview. Even in the aftermath of dealing with 2022 Pakistani flood, women and children were at a disadvantage. For example, according to Mehwish Abid, a Karachi-based Pakistani architect and multi-disciplinary artist, mosquito jali (net) beds that protect people from the threat of water borne diseases that follow a flood are often provided to men of the household, leaving women and children to suffer.

What can art do in the age of climate crisis? Artists provide us the opportunity to see what we do not recognize in daily life and tell stories that we would otherwise never know. What the New Delhi based photographer and visual storyteller Sharbendu De shows in his series, An Elegy for Ecology (2016-21) with photographs that represent the future living condition of human when we run out of clean air appear uncannily real; these photographs are shot with physical props and real people, and yet remain completely unreal. De’s vision, which may have been dismissed as a fantasy, fantasy world, or myth, even a decade ago may not be so far from our impending reality. De’s carefully constructed photographic images of a dystopian future urge us to acknowledge the necessity of reconfiguring our relationship with nature, as Ravi Agrawal suggests.16 Going to the marshland of Chibayish in Southern Iraq, Alia Farid’s video piece in the exhibition shows us the fragility of this ecosystem and the people whose lives are severely impacted by climate change.17 In addition to showing displacement and estrangement caused by climate change, Farid’s video art also presents us with a story of human-nature interconnectedness in which we witness the beauty of human-animal interspecies communications in the form of water buffalo herding and celebration of ecologically calibrated life, encouraging us to rekindle the human-nature relationship.

With extreme weather events occurring across the globe with increasing regularity, it is difficult not to see climate change as a catastrophe. While it is absolutely crucial to recognize and understand the causes and the impacts of this man-made disaster, fear alone does not help our planet and its life systems. By invoking the Points of Return rather than affirming that there is no return, and remembering the generative potential of climate events like floods as the indigenous Bengali concept of Bonna allows, and learning from each other’s stories, we may be able to embrace changing climates and learn to ebb and flow like water.

All sites mentioned in this essay are marked on this google Map.

ENDNOTES

1 The confluence of the Ganga River with the Brahmaputra/Padma River and the Meghna River (a major river of Bangladesh) before exiting into the ocean forms a mangrove delta called Sundarbans spread between India and Bangladesh. A transformed satellite view of Sundarbans is the dramatic cover image of the Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh.

2 any versions of the story exist. For a concise compilation of stories relating to Ganga, see Steven G. Darian, The Ganges in Myth and History (Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1978).

3 Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland Goldman eds.,The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: The complete English Translation ( Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021), 147-151.

4 According to Valmiki’s Ramayana, the tale of “the Descent of the Ganges brings one wealth, fame, long life, heaven, and even sons.” Goldman and Goldman trans. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki, p.151

5 See, for example, the interpretation of multivalent meanings in Padma Kaimal, “Playful Ambiguity and Political Authority in the Large Relief at Mamallapuram,” Ars Orientalis 24 (1994), pp. 1-27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4629457

6 The concept of “green water” is used in water-resource planning and management to refer to soil moisture derived from local rainfall that returns to the atmosphere as evaporation by vegetation. See Falkenmark and Rockström (2006).

7 Domestic water buffalos are indigenous to the South Asian sub-continent and common in West Asia. The water buffalo is the main dairy animal in Pakistan.

8 On Sufi yogis, see a recent study by Murad Mumtaz, Faces of God: Images of Devotion in Indo-Muslim Painting, 1500-1800 (Brill, 2023).

9 Radha Kapuria and Naresh Kumar, “Singing the River in Punjab: Poetry, Performance and Folklore,” South Asia 45(6), 1082. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00856401.2022.2124680

10 https://medium.com/subcontinental-elixir/paar-chanaa-de-29f360f509a

11 Henry David Thoreau, Walden with introduction by Bradford Torrey, holiday edition (Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1897), 276-278. Thoreau connects Ganga and Walden Pond in his book. See James L. Wescoat Jr., "From Nallah to Nadi, Stream to Sewer to Stream: Urban Waterscape Research in India and the United States," in Venugopal Maddipadi and Sugata Ray eds. Water Histories of South Asia ( Routledge, 2020): 135-157 and Raghunath Akarsh’s essay.

12 This identification is based on Dr. Katherine Eremin’s analysis. The analytical data on pigments mentioned here is available on https://mappingcolor.fas.harvard.edu/.

13 See Bhalla’s interview about his experience and difficulty in capturing the stillness in water in serial photographs.

14 https://bostonartreview.com/reviews/issue-06-profile-evelyn-rydz-jacqueline-houton/

15 The idea of connected waters is also behind the rise of Indian Ocean Studies in academia, which promotes interdisciplinary studies of the Indian Ocean world that explore ecology, climate, circulation and migration of people, goods and ideas, identifying little understood networks and cultural and political interconnectivities around the Indian Ocean and beyond

16 See the curator’s essay by Ravi Agrawal on https://www.desharbendu.com/an-elegy-for-ecology

17 For instance, see this Washington Post report about the impact of climate change in the region: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2021/iraq-climate-change-tigris-euphrates/