Water Spirits in a Desert:

Serpentine Imagery and Ritual in Ladakh

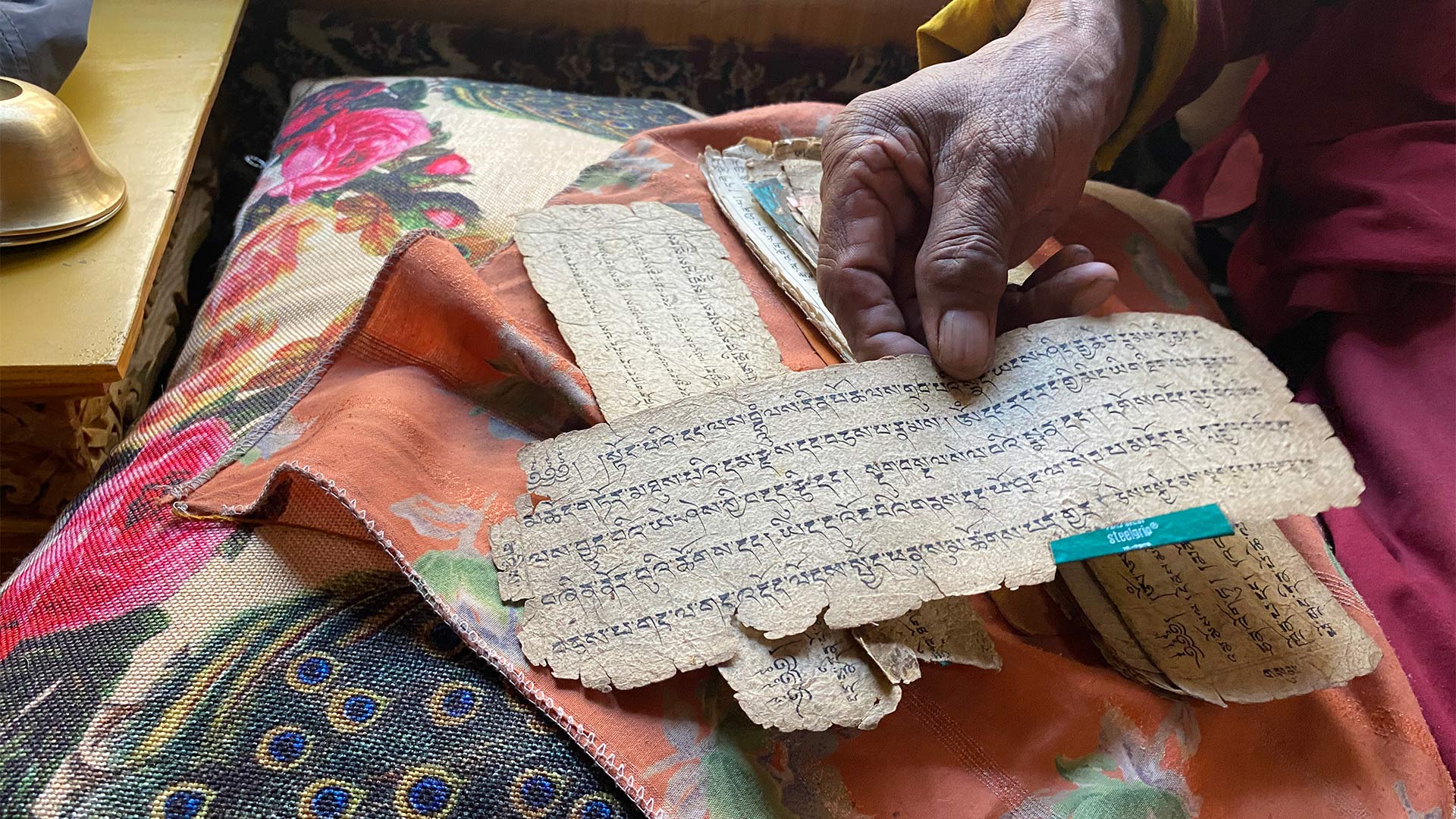

In a domestic setting, Khenpo Tsepel, a respected and elderly monk from Relagong village, performs a contemporary ritual dedicated to water spirits, lu (klu in Ladakhi and Tibetan) or naga ritual.

Across the high-altitude deserts of Ladakh, a region of western Himalayas in today’s India, water and water spirits are an essential aspect of village life and Buddhist ritual practice. Images of water spirits dwell in the fringes of visual programs. These spirits, known locally as lu (klu in Tibetan and Ladakhi)—commonly translated as naga (semi-divine hybrid beings from Indian Mythology who have human torsos with serpent tails), remind us of their contribution to Buddhist practice and role in navigating human relationships with the environment. To explore this intersection between water spirits, Buddhist ritual, and pictorial Buddhist space, this essay explores an extraordinary late twelfth-century painted Eight Great Nagas mandala (a visual representation of a cosmological universe that consists of deities and celestial beings enclosed by a circular boundary) and the contemporary ritual dedicated to the Eight Great Nagas both documented recently during my fieldwork (figure 1). Swinging between past and present, pictorial and ritual, we can begin to grasp the importance of water, water spirits, and water rituals in negotiating human relationships with Ladakh’s formidable environment to coexist harmoniously.

FIGURE ONE

Eight Great Nagā (kLu chen brgyad)

Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Maṇḍala in the central Mahavairocana Temple at Mangyu

Among the stunning murals that fill Mangyu’s central temple, one mandala in particular—a mandala of nagas—alerts us to the intrinsic connection between Buddhist space and the environment. While Mangyu is a modest village in central Ladakh, three remarkable late twelfth-century Buddhist temples connect the village to a network of early Buddhist sites in Ladakh and allude to the village’s distinguished medieval history.1 Two temples, each with towering three-story bodhisattva—Maitreya and Avalokitesvara, flank both sides of a larger central Vairocana temple. Inside each temple, exquisite wall paintings fill the visual field and clay sculptural programs emerge from the walls and into the devotees’ purview. In the central temple, a sculpted Buddha Mahavairocana (lit. great Vairocana, one of the five transcendental Buddhas of Esoteric Buddhism) accompanied by the other four Buddhas and goddesses resides in the main niche (figure 2). Painted mandalas, like the Eight Great Naga mandala, fill the temple’s remaining walls (figure 3).

FIGURE TWO

Mangyu’s multimedia main shrine in Mahavairocana temple. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

FIGURE THREE

Photo of Mangyu’s mural-covered walls inside the central Mahavairocana temple. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Entangled in each other’s arms, eight pairs of nagas—hybrid serpentine beings in Indic Mythology—encircle a seated Vajrapani.

Figure ONE detail Detail of Vajrapāni

Figure ONE detail Yellow nagā king, Kulika, and his consort

Figure ONE detail Detail of white naga king, Sankhapala and his consort. Photo: Rob Linrothe 2023

The seven-headed snake coiffure crowning Vajrapani’s visually echoes the attending nagas who frame him. With his hands, he makes the karaṇa mudra, a gesture of protection, and holds a vajra (lit. “diamond” or “thunderbolt” is an esoteric ritual instrument that signifies the harnessing of a thunderbolt’s power) in his outstretched right hand.2 The eight naga kings embrace their consorts but turn their heads toward Vajrapani to whom they extend their unique attributes toward him. These attributes and the variation in the nagas color—blue, white, red and yellow—enable us to identify each of them and their textual counterpart.3

Detail of aquatic scenes that fill the margis around the periphery of the Eight Great Naga mandala.

The combination of nagas and Vajrapani’s dominant centrality indicate that this mandala, the Eight Great Nagas (kLu chen brgyad), is derived from the Sarvadurgatiparisodhana (SDPS), a text of the Yoga Tantra class. The SDPS, translatable as the Elimination of All Evil Rebirths, emphasizes the role of Vajrapani in protecting the devotee from worldly and supernatural hard and for eradicating negative karma accumulated over lifetimes. The repetition of Vajrapani in the wall murals and his frequent positioning as the central deity in mandalas demonstrate the relationship between this temple and the SDPS tantra.4

The connection between this temple and the SDPS as well as the relationship between nagas and water recur throughout the temple’s visual program. While Vajrapani and naga imagery are common across Ladakh, images of the Eight Great Nagas mandala are very unusual. Typically, nagas appear among clusters of Hindu deities, in the eight charnel ground scenes, or beneath the Buddha paying homage. On Mangyu’s western wall, we find images of nagas in these more standard positions.

The nagas in the peripheral layer of a Mahavairocana mandala—depicted as a nagaraja (naga king), nagini (naga queen) and accompanying Varaha (Lord Viṣṇu’s boar avatar)— provide a wider context for understanding these semi-divine beings, their relationships with water, and their pan-Indic significance.

Figure FOUR Varaha, Lord Viṣṇu’s boar avatar, at Mangyu. Photo: Rob Linrothe 2004

The independent representations of the nagaraja and nagini demonstrate their ability to be stand-alone deities with the ability to protect and grant blessings (figure 5 and 6). Meanwhile, the naga in the Varaha image presents us with the temperamentality of nagas as water guardians (Figure 4). In the Varaha story, the world has descended into darkness because Bhu Devi, the earth goddess, was kidnapped and plunged into the depths of the cosmic ocean. Varaha bravely dives into the ocean and defeats a naga king to rescue the earth goddess. In the Mangyu image, Varaha sits atop the recently subdued naga. This story and pictorial detail underscore the pan-Indic connection between nagas and water resources as well as the necessity of cooperative nagas in negotiating favorable relationships with the environment.

Figure FIVE naga at the periphery of a Mahavairochana mandala on western wall in Mangyu’s central temple. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Figure SIX nagini at the periphery of a Mahavairochana mandala on western wall in Mangyu’s central temple. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

The contemporary Eight Great Naga Mandala ritual practice in Ladakh further demonstrates the interconnection between nagas, water resources, and the environment. Although the original SDPS was formulated in India with a more temperate climate in mind, the Eight Great Naga Mandala ritual has been adapted to accommodate the discrete needs and resources of Ladakh. All ingredients used in the ritual, such as barley flour, butter, milk, flowers, etc.—are sourced locally. The purpose of the mandala ritual, an offering to the nagas, ranges from agricultural and environmental to medicinal and personal.

Proper execution of the Eight Great Nagas Mandala ritual results in the benefactor gaining favor with the nagas, who in turn offer security, protection against snake bites, and bring rain for a bountiful harvest. “We [the nagas] will always provide the great being with constant protection, security, and cover… From time to time, we will shower with rain. We will produce all crops.”5 In Ladakh, there are no venomous snakes, and with its cold desert climate, there is little annual rainfall. Consequently, the purpose of the Eight Great Nagas mandala ritual has adapted to address alternative, naga rooted concerns, but the practice itself still closely adheres to the textual prescription.

Numerous agricultural traditions, Buddhist ritual practices, and behavioral codes of conduct have been developed to anticipate and prevent disturbing the lu (klu, the Ladakhi and Tibetan term for naga). In Ladakh, nagas are temperamental shape-shifting water spirits known as lu, who inhabit various corners of the natural world and can bestow great wealth. From streams and soil to trees and stones, lu are well-known for their abilities to both control water and wreck misfortune when perturbed. For instance, lu hibernate in the soil over the long winters, and before the first plow breaks through the soil, someone must awaken the spirit.6 Continuing without alerting and mollifying the spirit risks certain failure and catastrophe in the year’s harvest. Likewise, lu are known for their affinity for natural springs and contaminating a spring, even washing one’s hands in the spring, will disrupt the lu and can result in bodily afflictions, such as skin maladies, gastrointestinal discomfort, and joint pain. An unhappy lu can bring illness, hardship, and unending tragedy to an individual, family, or community. Performing the Eight Great Nagas mandala is one remedy for placating a disgruntled lu.

The Eight Great Nagas mandala ritual can be sponsored at either an individual or a communal level. An individual or family can request a monk to perform an Eight Great Nagas mandala ritual in their home to pacify a vengeful lu, such as a healing ritual, or to maintain the generous good graces of the lu. The Eight Great Nagas mandala ritual performed by Khenpo Tsewang Dorje that I observed was performed in a family home to maintain the family’s health and success through the coming year (figure 7).

Figure SEVEN A Khenpo in a private home reading from the Eight Great Nagas text. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Figure SEVEN B Khenpo in a private home reading from the Eight Great Nagas text. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Figure SEVEN C Khenpo in a private home reading from the Eight Great Nagas text. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Figure SEVEN D Khenpo in a private home reading from the Eight Great Nagas text. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Figure SEVEN E Khenpo in a private home reading from the Eight Great Nagas text. Photograph: Victoria Andrews, 2023

Conversely, in times of significant drought or famine, communities—either entire villages, monasteries, or fas phun (phas phun, an inter-family group of several families established by ancestors. They worship the same family deity and assist each other in times of need, such as for plowing, harvesting, births, and funerals)—can collectively sponsor a lu ritual.7 For example, in 2006 when there was a prolonged drought in the village of Lingshed, a village in central Ladakh, the monks performed the Eight Great Nagas mandala ritual as an offering to the lu to bring rain (figures 8-9).8 In the ritual, the monks make a temporary Eight Great Nagas mandala from barley flour and butter and offer medicines, milk, and flowers to the nagas.

Figure EIGHT Outdoor Rain bringing naga ritual in Lingshed Village. Photo: Rob Linrothe 2006.

Figure NINE Outdoor Rain bringing naga ritual in Lingshed Village. Photo: Rob Linrothe 2006.

Imagery, such as the wall painting at Mangyu, and the continued practice of the Eight Great Nagas ritual, enable us to bridge the gap between text and context, image and practice. Nagas control water, inhabit aquatic domains, and navigate between realms. In Ladakh, maintaining good relationships with the lu (nagas) is essential for sustaining balance and harmonious in the environment. As Ladakh continues to change—culturally and climatically—at rapid and unprecedented rates, these traditional relationships with the environment becoming increasingly important and strained.

ENDNOTES

1 Peter Van Ham. Heavenly Himalayas: the Murals of Mangyu and Other Discoveries in Ladakh. Prestel, 2011. Goepper, Roger, et al. Alchi: Ladakh's Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary: the Sumtsek. Shambhala; Distributed in the U.S. by Random House, 1996. Pal, Pratapaditya, and Lionel. Fournier. A Buddhist Paradise: the Murals of Alchi, Western Himalayas. 1st ed., R. Kumar, 1982.

2 For a more detailed explanation of vajras, see Robert Buswell, Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Pp. 259. And Robert Beer, The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. 1st ed., Shambhala, 2003. Pp. 87-91.

3 Although there the painted Eight Great Naga mandala at Mangyu deviates slightly from the text, we can still possible to identify most of the naga kings. Anata in the east is white in color and holds the stalk of a lotus in his right hand and a snake in his left. Takṣaka in the south is blue in color and holds a blue lotus in his right hand and a tortoise in his left. Karkota in the west is red in color and holds white waterlily in the right hand and a vajra in the left. Kulika in the north is yellow in color and holds white lotus in the right hand and a vase in the left. In the southeast, Vasuki, who is blue in color, holds a gem in the right hand and a lotus in his left. S̄aṅkhapala in the southwest is white in color holds a snake in the right hand and a conch shell in the left. In the northwest is the white naga king Padma, and he holds a lotus and a fruit in his left. Finally, in the northeast Varuṇa, who is white in color, holds a noose of snakes in his right hand and a lotus in his left. For more information, see Tadeusz Skorupski. The Sarvadurgatipariśodhana Tantra: Elimination of All Evil Destinies: Sanskrit and Tibetan Texts. Motilal Banarsidass, 1983.

4 Van Ham. Heavenly Himalayas.

5 Skorpuski. SDPS. Pp.55.

6 Ṛgveda 6.61.8, Griffith, Ralph T., trans., 631.

7 Ṛgveda 10.9.1–9, Griffith, Ralph T., trans., 391.

8 It appears that Gaṅgā significantly takes after the form and function of the Vedic and early Puranic River Sarasvatī. See Darian, Steven G. 1978. The Ganges in Myth and History. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 58–62; Bartmans, Frans. 1990. Āpaḥ, the Sacred Waters: An Analysis of a Primordial Symbol in Hindu Myths. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation, 259.